CONFERENCE COVERAGE SERIES

Clinical Trials on Alzheimer's Disease (CTAD) 2022

San Francisco, California

29 November – 02 December 2022

CONFERENCE COVERAGE SERIES

San Francisco, California

29 November – 02 December 2022

The top-line results last September from Eisai’s Phase 3 trial of the anti-amyloid antibody lecanemab galvanized the field, but scientists said they needed to see the data before passing judgement. Now they have. At the 15th Clinical Trials on Alzheimer’s Disease conference, held November 29 to December 2 in San Francisco and online, scientists presented detailed findings to a standing-room-only audience of some 2,000 people and many more on livestream. Four speakers reported that secondary and biomarker measures were consistent, and of similar magnitude to the effect on primary. Overall, lecanemab appeared to slow disease progression by about one-quarter, and caused the brain edema known as ARIA-E in one of eight participants. The data were published in the New England Journal of Medicine November 29, the same day as the presentation.

The audience responded positively. Many scientists praised the trial’s execution, and expressed relief that the presentations appeared thorough and transparent. “The Clarity trial is a landmark in AD therapeutic research, the culmination of over three decades of efforts across the field,” said Paul Aisen of the University of Southern California in San Diego. Randall Bateman of Washington University, St. Louis, presented the biomarker evidence, concluding that it indicates the treatment modified underlying biology. “These findings support the ability to change the course of Alzheimer’s disease,” he told Alzforum. Takeshi Iwatsubo of the University of Tokyo agreed, saying “This is a monumental event for patients.” All three are co-authors on the NEJM paper. Other researchers mentioned aspects of the trial design that strengthened their confidence in the findings, such as Eisai using separate medical teams to handle participants’ clinical trial evaluations and ARIA to minimize the risk of unblinding.

At the same time, researchers said the ARIA risks need to be taken seriously, and stressed that not all patients will be candidates for this therapy. Everyone agreed on the need to build on a small effect size by adding other therapeutic approaches and finding ways to give lecanemab earlier in disease.

Diverging Trajectories. People on lecanemab worsened more slowly on the CDR-SB than did people on placebo, resulting in a quarter less progression at 18 months. [Courtesy of Eisai.]

A Consistent Clinical Benefit

The 18-month Clarity trial enrolled 1,795 people with mild cognitive impairment or mild dementia due to AD, half of whom received 10 mg/kg intravenous lecanemab every two weeks. Eisai previously reported that lecanemab slowed decline on the primary outcome measure, the CDR-SB, by 0.45 points on the 18-point scale, or about one-quarter of the 1.66-point decline seen in the placebo group (Sep 2022 news).

In San Francisco, Christopher van Dyck of Yale School of Medicine in New Haven, Connecticut, fleshed out details on secondary measures. These mirrored the CDR-SB, with participants on lecanemab declining 1.44 fewer points on the ADAS-Cog14 and 0.05 fewer on the ADCOMS than the placebo group, for relative slowings of 26 and 24 percent, respectively. On a functional measure, the ADCS MCI activities of daily living (ADL), lecanemab put on the brakes by 2 points, or 37 percent. For all four clinical measures, the difference between lecanemab and placebo became statistically significant by six months and grew over time. On the CDR-SB and ADL, the slopes continued to diverge up to 18 months, whereas the difference between the curves appeared to stabilize on the ADAS-Cog14 at 15 months, and on the ADCOMS at 12.

“Because there is such mild decline in these patients over 18 months, it’s very difficult to see a positive signal,” noted Eric Musiek of Washington University in St. Louis, adding, “I’m impressed the signal is so clear, even if it is small in an absolute sense.”

The slightly larger effect on ADLs caught the interest of some scientists, since these can feel most important to participants. “[This] indicates that patients and families could benefit from slowing of observable functional worsening,” Joshua Grill of the University of California, Irvine, wrote to Alzforum (full comments below).

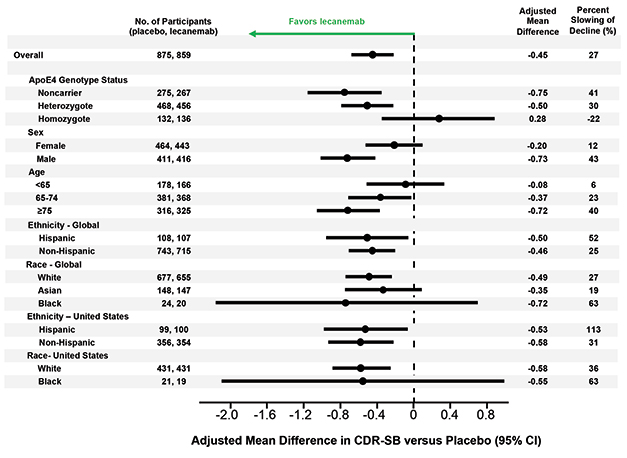

Left of Center. Lecanemab had similar effects in all subgroups examined, though men appeared to benefit more than women, older people more than younger, and APOE4 non-carriers more than carriers. [Courtesy of Eisai.]

Van Dyck also showed results from several sensitivity analyses that suggested the findings were not caused by confounding factors. In the treatment and placebo groups, 81 and 84 percent of participants, respectively, completed the trial, but dropouts did not affect the results. Imputing missing data and accounting for the COVID-19 pandemic did not change the data either. Nor did removing data from participants who developed ARIA-E, suggesting the positive results were not due to inadvertent unblinding of participants.

Likewise, subgroup analyses breaking down participants by age, sex, race, ethnicity, geographic region, disease stage, and use of symptomatic AD medications found treatment benefits across the board. Women appeared to benefit somewhat less than men, a potential difference that sparked discussion in the field. One possibility is that women have more advanced tau pathology at a given stage of cognitive impairment than men, making amyloid removal less effective for them, Maria Teresa Ferretti of the Women's Brain Project, a global non-profit based in Guntershausen, Switzerland, told Alzforum (Nov 2019 news).

The researchers also found a difference by APOE genotype. APOE4 carriers made up two-thirds of the cohort, and seemed to benefit less from lecanemab than noncarriers. In particular, the 15 percent of participants who carried two copies of APOE4 appeared to post no treatment effect on the CDR-SB, and but a small one on the ADAS-Cog14 and ADCS MCI-ADL. However, several scientists told Alzforum that they suspect the homozygote finding represents statistical noise. They pointed out that APOE4 homozygotes on placebo barely declined during the trial, muddying the ability to see a treatment effect in this small subgroup.

Colin Masters of the University of Melbourne, Australia, believes greater effects of lecanemab in APOE4 noncarriers make sense. “We know APOE4 leads to amyloid deposition starting earlier in life than in E4 noncarriers. I suspect the noncarriers had a better result because they started out with a lower amyloid burden,” Masters told Alzforum. He suggested letting trials run longer than 18 months to better detect effects in carriers.

The findings contrast with data from aducanumab, where more of the cognitive benefit in the positive EMERGE trial occurred in APOE4 carriers (see Nov 2020 news).

The Pesky Question: Does This Help Patients?

As with the FDA approval of aducanumab in June 2021, researchers at CTAD debated whether the measured benefit on these clinical tests is clinically meaningful. Sharon Cohen of the Toronto Memory Program, a site investigator for the Clarity trial, argued that it is. She noted that participants on lecanemab and their caregivers reported from one-quarter to one-half less worsening on measures of quality of life and caregiver burden compared to the placebo group. Looking at the data another way, the slower decline translated to a one-third lower risk of advancing to the next stage of AD during the trial, Cohen said.

More Time. Alzheimer’s disease progressed more slowly in people on lecanemab, delaying arrival of the next disease stage. [Courtesy of Eisai.]

This equates to a five- to six-month delay in disease progression, said Eric Siemers of Siemers Integration LLC (full comment below). Others noted this is similar to the benefit of acetylcholinesterase inhibitors, and wanted a Cohen’s d analysis of effect size for easier comparison with other treatments.

Researchers agree that the key question is what happens when people stay on lecanemab for longer periods. Will the clinical benefit persist, grow, as many argue, or diminish? Clinicians are eager to see data from open-label extension studies that might answer this question. “If the reduction in decline were to persist for, say, three to four years, I would expect it to be appreciated by families and patients. On the other hand, if the effect is not durable and fades within a year or so, there will be much less enthusiasm for its use, which after all is somewhat arduous,” David Knopman of the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota, wrote to Alzforum (full comment below).

Amyloid as Surrogate?

As expected, lecanemab’s slashing of plaque was dramatic. In Clarity, participants started with an average amyloid PET of 76 centiloids at baseline. This rose by four in the placebo group and dropped by 55 in the treatment group, for a difference of 59 centiloids at 18 months. The divergence between groups became statistically significant at three months, and another three months later clinical measures started changing. Participants on lecanemab ended up with an average of 23 centiloids, which is below the threshold for amyloid positivity typically set at 25. Put another way, two-thirds of the treatment group became PET amyloid-negative at 18 months.

Roger Nitsch of Neurimmune, Switzerland, believes there is also a threshold effect for clinical benefit. In a keynote talk at CTAD, he noted that positive trials of anti-amyloid antibodies, such as Clarity, aducanumab’s EMERGE, and donanemab’s TRAILBLAZER, all brought plaque below 25 centiloids. Negative trials, such as aducanumab’s ENGAGE and the recent GRADUATE studies of gantenerumab, did not. “We have to lower amyloid load to 25 or less to get a clinical effect,” Nitsch proposed.

Others concurred that the relationship between amyloid removal and clinical benefit may not be linear, but stepwise. Eisai has not yet shown data on the correlation between how much of a person’s plaque vanished and their clinical response in Clarity. Ron Petersen of the Rochester Mayo Clinic said that more data are needed on whether it makes a difference how fast amyloid was removed.

At CTAD, researchers debated whether the Clarity results are strong enough to validate plaque removal as a surrogate biomarker for disease slowing. Maria Carrillo of the Alzheimer’s Association made a case for this; others want to see more data. Van Dyck noted that plaques could well be a stand-in for smaller aggregates, which might be the toxic species responsible for cognitive decline. Grill suggested that downstream markers of tangle burden and neurodegeneration may be more important for predicting the cognitive effects of treatment.

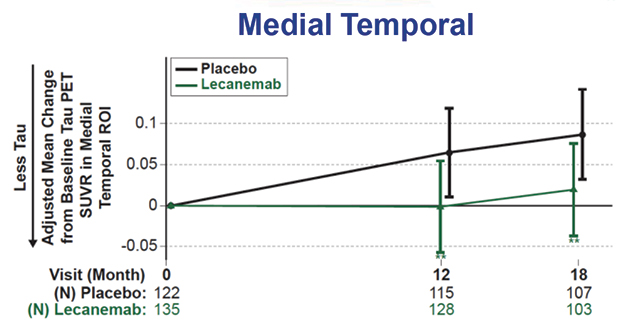

Tangle, Inflammation Markers Down. Tau tangle spread slowed on lecanemab (top), while a fluid marker of astrogliosis fell (bottom). [Courtesy of Eisai.]

Alzheimer’s Biomarkers Down, Neurodegeneration Signals Mixed

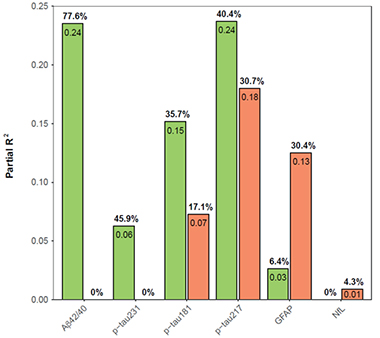

Regarding those markers, CTAD provided a wealth of data. Bateman reported that on lecanemab, the Aβ42/40 ratio rose by about 60 percent in cerebrospinal fluid and 10 percent in plasma, while p-tau181 dropped around 16-18 percent in both. These measures became statistically different from placebo at six months, in tandem with the clinical benefits. Tau PET showed a slowing but not stoppage of tangle accumulation in the medial temporal lobe, and trends toward slowing in other brain regions, with the PET signal increasing about half as much as in controls. The astrogliosis marker GFAP fell about 15 percent on lecanemab, but rose 10 percent in those on placebo.

“I was particularly pleased to see the significant fall in plasma GFAP levels,” Dennis Selkoe of Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, wrote to Alzforum. “This suggests a notable amelioration of an inflammatory component that is increasingly recognized as a main feature of AD.”

Neurodegeneration markers gave a more ambiguous picture. CSF total tau fell about 4 percent on lecanemab, while rising 15 percent on placebo. Neurogranin, which reflects synapse loss, normalized as well, falling about 15 percent. On the other hand, plasma NfL only trended toward improvement on lecanemab, while CSF NfL did not change.

As has been seen with other amyloid immunotherapies, structural MRI revealed more shrinkage of whole brain and of cortical thickness on lecanemab, and an expansion of the brain's fluid-filled ventricles. Curiously, however, atrophy in the much smaller hippocampal region slowed. Brain atrophy used to be considered bad, and is used routinely as a diagnostic aid for many brain diseases. Alzheimerologists still do not know what to make of these findings. An early hypothesis—that gray matter shrinkage may reflect amyloid removal—is not in vogue anymore, but nothing else has emerged in its place. Knopman cautioned that the increase in ventricle size in particular deserves further study. “We are willing to ignore this finding now because we have a clinical benefit, which is the gold standard. But we need to keep it in mind,” he said.

Overall, the data support the idea that lecanemab modifies underlying biology, Bateman said. Eric Reiman of Banner Alzheimer’s Institute in Phoenix, whose abiding interest is in enabling prevention, believes these data will help facilitate future prevention trials for a range of drugs by clarifying how biomarker changes predict clinical outcomes.

ARIA Lower, but the Risk Is Real

Safety is a major concern for the widespread use of any amyloid immunotherapy. Eisai and Biogen previously announced that 12.6 percent of people taking lecanemab developed the brain edema known as ARIA-E. In San Francisco, Marwan Sabbagh of the Barrow Neurological Institute in Phoenix showed details. About one-quarter of ARIA-E cases came with symptoms, which were typically mild and cleared up within three to six months. Three people in the trial had severe symptoms, though Sabbagh did not identify what they were.

As expected, a person's ARIA-E risk was driven by his or her APOE genotype. One-third of APOE4 homozygotes developed ARIA-E, compared to 10 percent of heterozygotes and 5 percent of noncarriers. For reference, in aducanumab’s Phase 3 trials, those percentages were 66, 36, and 20 (Dec 2021 news).

Researchers said the overall risk/benefit calculation favors lecanemab. “I view the safety profile to be acceptable,” Grill said. Nick Fox of University College London agreed. “Any risk is clearly important, but I believe many of my patients would be willing to take such a risk,” he wrote (full comment below).

Nonetheless, they cautioned that clinicians will need to understand well what concurrent illnesses might magnify their patients’ risk so they can counsel them appropriately. Recent reports of two deaths from brain hemorrhage in the lecanemab open-label extension have broadly publicized the issue. One was a man with atrial fibrillation who was taking blood thinners; the other, a woman with cerebral amyloid angiopathy who received tissue plasminogen activator after a stroke (see Science story).

Neither death has been definitively linked to lecanemab, but they have reignited discussion about whether blood thinners and tPA should be contraindicated for people taking lecanemab. Anticoagulant use was allowed in the Clarity trial, in part because Eisai felt it needed to collect these data to learn about the issue, Eisai’s Mike Irizarry told the audience during his presentation. Macrohemorrhages, defined as any brain bleed larger than 1 cm, came in at 0.7 percent in the treatment group, higher than the 0.2 percent in the placebo group. For people on anticoagulants, the rate of macrohemorrhage on lecanemab was 2.4 percent, a more than threefold increase.

“tPA and anti-Aβ antibodies perhaps should not be given to the same AD patient, especially in the presence of CAA,” said Mathias Jucker, Hertie Institute, Tuebingen. Twenty years ago, Jucker’s group described how both tPA and Aβ immunotherapy induced cerebral bleeding in mouse models with CAA, though the scientists did not test the combination (Winkler et al., 2002; Pfeifer et al., 2002).

Stepping Stone to Disease Modification?

With a decision on accelerated approval of lecanemab scheduled by January 6, researchers expect the drug to become clinically available in 2023 (Jul 2022 news). Fox noted that this will create a tremendous challenge for healthcare systems, which at present lack the resources to do the diagnosis, counseling, imaging, IV infusions, and MRI monitoring needed. Most clinics are unprepared to roll out amyloid immunotherapy quickly at a large scale.

Even so, researchers at CTAD liked that the Clarity cohort was more representative of the general AD population than were previous trial cohorts. It included 22.5 percent Hispanic and 4.5 percent black participants. The age range was broad, from 50 to 90 years old, and inclusion criteria were intentionally liberal, allowing people with common conditions such as hypertension, diabetes, obesity, hyperlipidemia, and heart disease to join. Selkoe noted that about one-fourth of AD patients in the general population would meet the Clarity inclusion criteria, suggesting many could qualify for lecanemab treatment.

Still, clinicians are cautious. “If I were to start using this in my clinic, I would target it at healthier patients with positive biomarkers but milder symptoms, less atrophy on MRI, no microhemorrhages, and no anticoagulation,” Musiek wrote. “Patients will need to be motivated, reliable, and have good access and support (as well as insurance) to successfully receive this therapy and keep up with the MRI monitoring.”

The Alzheimer’s Association in 2021 announced a registry study, dubbed ALZ-NET, to track the long-term risks and benefits of disease-modifying AD therapies (Nov 2021 conference news; Aug 2022 conference news). In San Francisco, Carrillo noted that ALZ-NET enrolled its first patient November 1. So far, all participating clinics are on the east coast of the U.S.; the association invites additional institutions to join.

The FDA already has a mechanism to ensure that risky drugs are safely administered. The Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy (REMS) educates physicians on how best to use drugs with potential deleterious effects, and maintains a central database to track outcomes. Jason Karlawish of the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, suggested the FDA require lecanemab use REMS. “The risk/benefit assessment is an ethically challenging Gordian knot. FDA and CMS should collaborate to assure this complicated drug’s transition from research into practice is net beneficial,” he wrote (full comment below).

In anticipation of approval and, potentially, insurance coverage, changes are already being set in motion across the research field. For example, leaders of longstanding observational cohorts that never disclosed amyloid status to their participants, such as AIBL and others, anticipate contacting them to inform them they can now find out their status and go on lecanemab if appropriate. Down's syndrome researchers are considering running trials in the readiness cohorts they have been building among this population. Scientists at drug companies across the field are starting to prepare for testing their investigational drugs against lecanemab as background medication. And aducanumab researchers are hinting that—just you wait—this antibody is going to come off the sidelines in 2023, as well.

All researchers Alzforum spoke with stressed that lecanemab and other amyloid immunotherapies represent the beginning of disease-modifying therapies. Many estimate a 30 percent slowing may be the most that can be achieved with amyloid removal alone in a symptomatic population, especially in the presence of mixed pathology. They emphasized the need to explore anti-amyloid drugs in presymptomatic populations with biomarker evidence of only amyloid pathology, or amyloid and tau pathology. All eventually want active vaccines to reduce cost and open treatment to large populations across nations. Finally, they urge combination trials of different therapeutic approaches to build on this first signal. At CTAD, Lefkos Middleton of Imperial College London said, “We need to celebrate what we have, but keep investigating AD biology to find treatments that make a big difference.”

Also at CTAD, Selkoe, Gil Rabinovici of the University of California, San Francisco, and several others, met to discuss how to rally support for lecanemab among policymakers in the U.S. and internationally. They drafted a joint letter that is being sent around within the community along with a sign-on form. The signature processes is being coordinated by Robert Egge at the Alzheimer's Association, which may use the letter to influence the U.S. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. If the FDA approves lecanemab in 2023, the CMS will make a coverage decision that private insurers are likely to follow. —Madolyn Bowman Rogers & Gabrielle Strobel

For many people living with dementia and their caregivers, the worst symptom of the disease is not memory loss, but agitation. Whether it comes out as verbal insults or physical violence, agitation in people with Alzheimer's disease is often what drives distraught carers to institutionalize their loved one. No safe, effective treatment exists. Against this bleak backdrop, positive findings from Phase 3 studies of brexpiprazole, a drug approved for schizophrenia, received a warm welcome at the Clinical Trials in Alzheimer’s Disease meeting, held November 29 to December 2 in San Francisco. According to Nanco Hefting of Lundbeck in Copenhagen, the drug curbed agitation in AD, meeting the primary endpoint in a third Phase 3 trial. Researchers welcomed the positive findings, but also called for continued monitoring to ensure the drug is safe in this vulnerable population.

Curiously, the benefit of brexpiprazole over placebo paled in comparison to the effect of merely participating in the trial, as agitation eased substantially in both the treatment and placebo groups. This finding jibes with results of another agitation trial presented at the conference, which tested the anti-depressant mirtazapine in people with AD. Though that drug worked no better than placebo, agitation dropped substantially in both groups throughout that trial, as well. Together, the findings point to the power of quality medical care and social support. These factors constitute a level of attention rarely received outside of a clinical trial.

The lack of proven treatments to calm agitation in AD has led to much off-label use of sedatives. These come with a bevy of side effects in people with dementia, including falls and fractures, worsening cognitive decline, and cerebrovascular problems, not to mention low effectiveness. “When considering pharmacotherapy for these patients, the goal is to treat the agitation, and not to sedate the patient,” Hefting told the audience.

To that end, Lundbeck teamed up with Otsuka Pharmaceuticals back in 2013 to evaluate brexpiprazole for the treatment of agitation in people with AD. Brexpiprazole is a successor to Otsuka’s aripiprazole, marketed as Abilify or Aripiprex, a dopamine D2 receptor agonist that is widely used to treat schizophrenia and related affective disorders. Compared to its predecessor, brexpiprazole interacts with a broader range of neurotransmitter receptors. In people with schizophrenia, the drug is considered neither activating nor sedating.

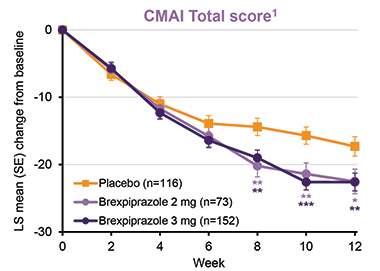

Over the past decade, the companies have completed three Phase 3 trials for AD-associated agitation. Results from the first two trials were reported in 2018 and subsequently published together (Grossberg et al., 2020). The first trial tested safety, efficacy, and tolerability of 1 or 2 mg brexpiprazole, or placebo, daily for three months in 420 participants in the United States, Europe, and Russia. The second enrolled 270 participants and used a flexible dose design, with doses ranging from 0.5 mg to 2 mg per day. Participants with AD dementia were included if they scored at least four points on the aggression/agitation domain of the NIH neuropsychological inventory (NPI-NIH-A/A). Change on the Cohen-Mansfield Agitation Inventory (CMAI) at 12 weeks served as the primary endpoint for both trials.

Trial 1 met its primary endpoint, curbing CMAI scores at 12 weeks. The second trial missed the endpoint, although a post hoc analysis suggested an easing of agitation among those who had received the 2 mg dose. Brexpiprazole also appeared to be effective among participants who had displayed frequent aggressive behaviors—either verbal or physical—at baseline. In both trials, participants taking brexpiprazole fared better than those receiving placebo on the Clinical Global Impression-Severity of Illness (CGI-S), a secondary measure of agitation completed by the clinician.

Based on their learnings from the first two trials, the researchers initiated a third Phase 3 trial that compared 2 mg and 3 mg daily doses of brexpiprazole to placebo. In addition to the inclusion criteria for the first two trials, the third trial required participants to meet criteria for CMAI Factor 1, meaning they frequently displayed aggressive behaviors. The trial enrolled 345 participants, and randomized 117 to placebo and 228 to brexpiprazole, of whom 75 received 2 mg and 153 received the 3 mg daily dose. CMAI scores dropped substantially in the placebo and brexpiprazole groups throughout the trial. By eight weeks, the brexpiprazole group had edged out the placebo group. By the end of the trial, CMAI scores had dropped by 22 points in those taking either dose of brexpiprazole, and by 17 points in the placebo group. The same pattern was observed for scores on the CGI-S, a key secondary endpoint.

Easing the Mind. Over a 12-week trial, agitation scores dropped in participants in both the placebo and brexpiprazole groups. For the final timepoints, brexpiprazole was significantly more effective than placebo. [Courtesy of Nanco Hefting, Lundbeck.]

While brexpiprazole eased all manner of agitated behaviors, it was most effective at calming the most severe ones: the drug reduced the frequency of overtly aggressive acts more than of verbal agitation or physically nonaggressive behaviors.

Were these benefits clinically meaningful? To address this, the researchers compared the number of participants in the placebo versus the combined treatment group whose CMAI scores dropped by at least 20, 30, or 40 percent. They found that a significantly greater proportion of participants in the treatment groups reached each of these response thresholds. For example, CMAI scores dropped by at least 20 percent in 68 percent of participants receiving brexpiprazole, compared with 47 percent of participants in the placebo group.

Brexpiprazole was generally well-tolerated and safe. This was true whether analyzing the third trial alone, or pooled safety data from all three Phase 3 trials. No adverse event had an incidence of more than 5 percent, and none occurred significantly more frequently in the brexpiprazole group. One notable exception was death—across all three trials, six people (0.9 percent) on brexpiprazole died, compared to one person, or 0.3 percent, on placebo. Hefting said that the deaths were deemed unrelated to the drug. Importantly, brexpiprazole did not sedate participants.

In a panel discussion following Hefting’s presentation, panelists largely commended the findings. Noting the extensive off-label use of drugs in people with AD and agitation, Alireza Atri of the Banner Sun Health Research Institute in Arizona, said “Anything that is safe and effective is welcome.” “Generally, patients and families are on knife’s edge when this happens,” Atri said, adding that agitation is often what breaks a family's resolve. Atri was encouraged by the safety data, but on efficacy would have liked to see data on the drug’s effect size, and on how much it improved the quality of life of individual patients and their caregivers.

Clive Ballard of the University of Exeter, U.K., was pleased to see a trial in a population that is notoriously difficult to recruit, and that included institutionalized patients. Ballard, too, wanted more effect size data, noting that a Cohen’s d value would have been helpful. Ballard added that while the overall safety profile of brexpiprazole appeared superior to other atypical antipsychotic drugs, he remained concerned about the elevated mortality reported among those taking brexpiprazole. He suggested monitoring mortality and safety among those prescribed the drug in the future. He also noted that at an average of 74, the trial participants were a decade younger than the average nursing home resident with dementia. “I would like to see safety data in an older, frailer group,” he said.

A more positive view came from Pierre Tariot, also at Banner, who said he thought the jury had been a bit sober so far. “We had efficacy without all the toxicity that has plagued the other drugs we’ve been studying for agitation,” he said. “This sounds like a major advance.” Tariot asked what distinguished brexpiprazole from its predecessor, aripiprazole, which has an unclear track record in easing agitation in people with AD and causes more side effects. Hefting said brexpiprazole’s edge may come from its broader, more balanced relationship with neurotransmitter receptors. It partially agonizes serotonin 5-HT1A receptors and dopamine D2 receptors, while quelling signaling from serotonin 5-HT2A and noradrenaline receptors.

At the end of the discussion, Anton Porsteinsson, University of Rochester, New York, pointed out the elephant in the room: While much focus was given to the five-point difference between the placebo and drug groups on the CMAI, a much larger effect came from simply participating in the trial, as CMAI scores dropped by 17 points in the placebo group. “We have a very substantive placebo response,” Porsteinsson said, “and we won’t be able to replicate it in clinical practice because we can’t give the degree of attention that we do in clinical trials.”

Sube Banerjee of the University of Plymouth, U.K., calls this apparent “placebo effect” a “treatment-as-usual effect,” referring to the benefits that come with the care given to all participants in a clinical trial. Few people have access to the level of care deemed “usual” in the context of a clinical trial, and when they do, it can have a stronger effect on agitation than any drug, he suggested (see full comment below).

Making Treatment-as-Usual More Usual

At CTAD, Banerjee presented published findings from the SYMBAD trial, which evaluated mirtazapine in people with AD and agitation (Banerjee et al., 2021). This antidepressant is widely prescribed for off-label use in this population. The trial enrolled, from 26 U.K. centers, 204 people with AD whose agitation was unresponsive to nondrug treatment. Nearly half lived in a care home; their average age was 82. Over 12 weeks, CMAI scores dropped by 12 points in both the placebo and mirtazapine groups. “There was considerable improvement, but it had nothing to do with being given mirtazapine,” Banerjee told the audience.

Why did being in the trial work so well? For one, Banerjee noted that agitation in AD can arise from many sources. They can be unmet physical needs, such as hunger, thirst, or pain. They can be an overcrowded, noisy, too stimulating, or too boring environment. They can be psychosocial issues such as stress, loneliness, depression, or lack of purpose. They can be relational issues with the family, caregivers, and other residents in a care home. Dementia itself was last on his list of sources of agitation, and Banerjee said this was by design. “The assumption that the agitation is caused by the dementia itself, rather than societal, family, or environmental factors to do with dementia, must be tested,” he said. “When you start looking at all of these causes of agitation, what is the likelihood that a drug of any kind would help with these unmet needs?”

Banerjee believes agitation in dementia requires a multipronged approach, noting that small studies have demonstrated that nondrug interventions, which take time to engage with the person with dementia, help reduce agitation (Livingston et al., 2014). The trouble is, such mental and social support services are underfunded and unavailable to most people with dementia who live at home or in facilities.

“Health systems would be well advised to focus on providing good-quality, nondrug psychosocial care and support for those with agitation in dementia rather than seeking to use medication to deal with these complex states,” Banerjee wrote to Alzforum. “Drugs should be a last line treatment in all but the most severe cases.”—Jessica Shugart

No Available Further Reading

It’s a truism that a more affordable way to ever rid the world of Alzheimer's than therapeutic antibodies would be the other kind of immunotherapy. Remember vaccines? After the first attempts tanked in the 2000s, attention pivoted sharply to antibodies, though more recently, a new generation of active immunotherapy attempts has sprung up, and two of them strutted their stuff at the Clinical Trials in Alzheimer’s Disease conference, held November 29-December 2 in San Francisco.

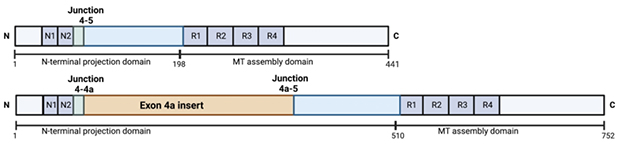

First, AC Immune. After its first anti-tau vaccine garnered but a meager immune response, scientists there added more kick and tried again. This did the trick, according to interim findings from a Phase 1b/2 trial presented at CTAD. AC Immune's Johannes Streffer reported that ACI-35.030, which features tau peptides anchored to a liposomal bilayer along with adjuvants, elicited a rapid and durable antibody response specific to phospho-tau and paired helical filaments in people with Alzheimer's. A protein-conjugated vaccine directed against the same tau peptide triggered a sluggish response that was less specific for these disease-associated forms of the protein, Streffer said. Both vaccines seem safe and well-tolerated thus far. AC Immune is working with Janssen to move ACI-35.030 into larger trials.

The new findings come 2.5 years after weak antibody responses to the company's first stab at a liposomal anti-tau vaccine (Apr 2020 news). Called ACI-35, the original featured a liposomal bilayer to which 16 copies of a synthetic tau fragment phosphorylated at residues S396 and S404 were anchored, along with a lipopolysaccharide-derived adjuvant called monophosphoryl lipid A. After B cells in AD patients appeared to shrug this off, the scientists added a second adjuvant and packed on a non-target T cell epitope. The latter served to rally helper T cells to stoke tau-specific antibody production by B cells. At CTAD, Streffer disclosed neither the T cell epitope nor the second adjuvant used in the so-called SupraAntigen platform.

Bells and Whistles. ACI-35.030 includes a phospho-tau peptide anchored to a liposomal bilayer, along with two adjuvants and a non-target T cell epitope to rally B cells to churn out antibodies against phospho-tau. [Courtesy of Johannes Streffer, AC Immune]

Streffer showed interim findings from a Phase 1b/2 trial of the improved vaccine, dubbed ACI-35.030, in people with early AD. The trial tested three successively higher doses. For each, six participants received the vaccine and two, placebo. Four jabs were spread out over 50 weeks, followed by safety follow-up until 74 weeks. All three doses appeared safe and well-tolerated, Streffer said

Measuring serum antibody titers against phospho-tau, tau paired helical filaments, and unphosphorylated tau two and eight weeks after each injection, the scientists found that all participants mounted an antibody response to phospho-tau two weeks after the first injection across all three dose groups. About 70 percent had mounted a response to PHFs, while 80 percent had responded to non-phosphorylated tau. At this early time point, antibody titers for p-tau topped those of the other two forms by an order of magnitude.

Importantly, as the trial went on, the antibody response shifted even further toward disease-associated forms of tau. Focusing on the mid-dose cohort for later time points, Streffer reported sustained antibody responses to p-tau and PHFs over a year, while antibodies specific for non-pathological tau waned significantly, nearing levels in the placebo group by the end of the trial. Streffer concluded that ACI-035.030 triggered a rapid, sustained antibody response to pathological forms of tau, which skewed toward those forms over time.

Streffer also reported findings from a similarly designed trial of JACI-35.054, a vaccine in which the same peptide of tau was linked to a carrier protein along with two adjuvants. JACI-35.054 also triggered an antibody response in participants with early AD; however, it required more jabs to evoke the response, and the antibodies were not specific for pathological forms of tau. Based on these findings, AC Immune/Janssen picked ACI-35.030 for future trials.

As this liposome vaccine graduates from Phase 1, another contender is about to enter it. At CTAD, Lon Schneider, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, showed preclinical findings and a proposed Phase 1 trial design for AV-1980R/A, an anti-tau vaccine developed by Michael Agadjanyan of the Institute for Molecular Medicine in Huntington Beach, California. Researchers at USC; Banner Alzheimer’s Institute in Phoenix; at University of California, San Francisco; and at the University of Gothenburg in Sweden are working on the preclinical and clinical development of this vaccine, which is funded with a cooperative grant from the National Institute on Aging.

AV1980R/A is a recombinant protein vaccine. It uses a universal immune-stimulating backbone called Multi-TEP, which Agadjanyan and colleagues developed to target mischievous proteins involved in neurodegeneration. Versions targeting Aβ and α-synuclein are also in the works (Zagorski et al., 2022; Kim et al., 2022; Aug 2021 conference news). Multi-TEP straps an antigen of choice to a series of antigenic peptides from common pathogens that most people have been exposed to or vaccinated against. These peptides rally memory T helper cells, and the hope is that, once revived, this pep squad will bolster anti-tau antibody production by B cells. Multi-TEP was designed to rouse the flagging immune systems of older people, which tend to have memory T cells but few naïve T cells.

AV1980R/A targets a stretch of tau’s N-terminus. It includes three tandem copies of residues 2 to 18, which contain the protein’s phosphatase-activating domain (PAD). This domain reportedly is important for tau's aggregation-mediated toxicity and becomes exposed once tau starts to aggregate (Combs et al., 2016). These two factors inform the rationale behind this choice of tau peptide for AV1980R/A, even as previous therapeutics antibodies taking aim at tau's N-terminus have failed in the clinic. Agadjanyan and colleagues pointed out that antibodies spurred by AV-1980R/A recognize different epitopes than those targeted by other N-terminal antibodies, including semorinemab, tilavonemab, and gosuranemab.

So far, preclinical findings in rodents and nonhuman primates indicate that the vaccine provokes a robust anti-tau antibody response without toxicity (Hovakimyan et al., 2022; Hovakimyan et al., 2019; Davtyan et al., 2019). In a nonhuman primate study published last October, AV1980R/A activated a broad repertoire of Multi-TEP-specific T helper cells, which spurred B cells to churn out antibodies specific to the PAD region of tau. These, in turn, latched on to tau tangles and neuropil threads from AD brain samples, but not to tau in brain sections from non-AD controls. Based on these findings, the scientists propose moving AV1980R/A into human trials.

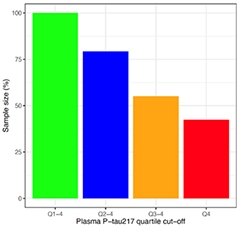

The idea is to use the vaccine for primary prevention in healthy adults at risk for AD, Schneider said. For this first study, Schneider said cognitively normal people in the preclinical stages of AD will be enrolled based on the PrecivityAD2 biomarker test, which takes into account the blood Aβ42/40 ratio and p-tau217, as well as ApoE genotype. The multiple ascending dose study will test three doses of the vaccine against placebo. Participants will receive four doses of the vaccine or placebo over 36 weeks, followed by a 56-week follow-up. This first-in-human study will test safety and tolerability of the vaccine, and will also measure antibody and T cell responses, and multiple AD blood biomarkers, Schneider proposed. The vaccine currently awaits IND approval by the FDA, which is anticipated by May 2023.—Jessica Shugart

No Available Further Reading

Can a cognitive test taken on a computer, in the comfort of one’s home, tell neurologists as much as a pencil-and-paper test done in a clinic? Yes, according to two researchers who presented their work at the Clinical Trials on Alzheimer’s Disease conference, held November 29 through December 2 online and in San Francisco. Jessica Langbaum of the Banner Alzheimer's Institute in Phoenix reported that scores from five cognitive tests given over video chat tightly correlated with scores of those same tests given face-to-face. Likewise, Paul Maruff of the Australian neuroscience technology company CogState found that people who had mild cognitive impairment or preclinical AD performed similarly on in-person and remote versions of two cognitive tests. Knowing that both testing modalities are equal is crucial as clinical trials move to decentralized designs.

“This is very important work, and we need to continue validating remote testing for clinical use and trials,” wrote Dorene Rentz, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston (comment below).

Previously, researchers had found that new memory tests given via smartphone correlated with scores of in-clinic assessments (Nov 2020 conference news). Ditto for the first attempt at moving the clinical dementia rating (CDR) online (Dec 2021 conference news).

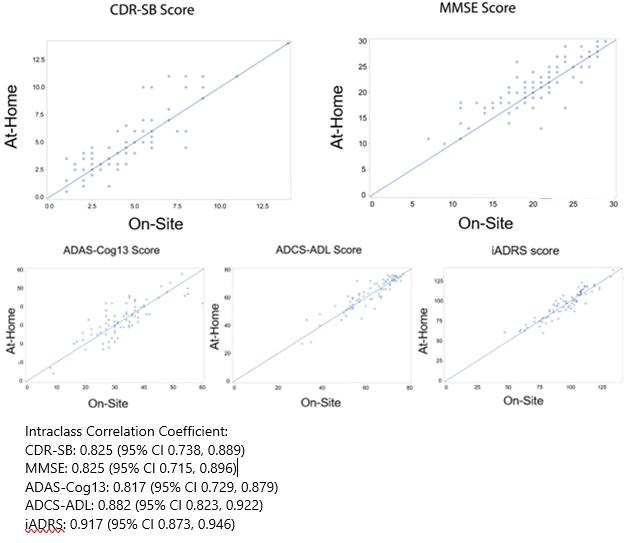

Now, Langbaum also found that the CDR and other commonly used cognitive tests, when completed through a computer screen, detected dementia as well as did tests administered face-to-face. She compared in-clinic to online administration of five tests: the CDR sum of boxes (CDR-SB), Mini-Mental State Exam (MMSE), Alzheimer’s Disease Assessment Scale–Cognitive Subscale 13 (ADAS-Cog13), integrated Alzheimer’s Disease Rating Scale (iADRS), and Alzheimer’s Disease Cooperative Study–Activities of Daily Living (ADCS-ADL).

Langbaum tested 82 people who had MCI or mild-to-moderate AD from the TRAILBLAZER cohort after they finished taking the study drug donanemab. Half of the participants were guided through the cognitive tests at first in-person and then over video chat four weeks later; half did the opposite. For the remote assessments, participants received a paper-and-pencil version of the cognitive tests that have written components, a laptop, a device that provides Wi-Fi, and a wide-angle web camera. The camera helped the test raters ensure participants did not write down answers and had no distractions while completing the at-home tests. Then the participants were trained how to use each device. “This work showed that you can distribute complex technology and rely on folks to set it up and use it, then get good-quality data,” Maruff wrote to Alzforum.

On all five tests, remote and in-clinic scores strongly correlated, with coefficients between 0.82 and 0.92 out of a perfect 1.0 (see image below). Langbaum concluded that these at-home and in-person cognitive tests were equivalent.

Big 5 Good To Go. In-clinic (x-axis) and remote (y-axis) scores on the CDR-SB, MMSE, ADAS-Cog13, ADCS-ADL, and iADRS correlated closely. [Courtesy of Jessica Langbaum, Banner Alzheimer’s Institute.]

Maruff found a similarly strong correlation between in-clinic and remote CDR-SB scores from people who had MCI, with a correlation coefficient of 0.86 (see image below). He also saw close alignment of in-person and computerized tasks from the Preclinical Alzheimer’s Cognitive Composite (PACC) in people who are cognitively intact but have amyloid plaques. “Unlike the CDR, the PACC requires real-time interactive administration with visual-manual requirements, such as the digit-symbol substitution test, so our work focused on how such tasks could be administered and scored over video chat,” Maruff told Alzforum.

Maruff and colleagues studied 31 people who had preclinical AD and 23 who had prodromal AD from the Australian Imaging, Biomarker, and Lifestyle (AIBL) and Australian Dementia Network (ADNeT) cohorts. Half completed the in-person tests and then the remote assessments two weeks later; half did the remote then in-clinic tests.

During the at-home assessment, the participant video chatted with a test rater who verbally administered the CDR-SB and PACC international shopping list test. Then, the rater guided the participant through computerized versions of two more PACC tasks: the digit-symbol substitution test and the visual paired association learning test. For these, the participant completed example tasks before the real ones, with the computer advancing only after the participant got the task correct. Results from the three PACC tasks were summed to give the total score.

Digital and pen-and-paper PACC scores strongly correlated, yielding coefficients of 0.81 and 0.91 for preclinical and prodromal AD, respectively (see image below). Maruff concluded that, whether administered remotely or in person, the PACC tasks and CDR-SB can sense subtle cognitive impairment.

In Sync. In people with prodromal AD (black, left), CDR-SB scores from the remote (x-axis) and in-person (y-axis) versions correlated tightly. Ditto for remote and in-clinic scores on the PACC (right) in both prodromal and preclinical (open circles) AD. [Courtesy of Paul Maruff, CogState.]

The correlation of digital and face-to-face cognitive tests also held for people who had frontotemporal dementia. Adam Staffaroni of the University of California, San Francisco, had previously reported that scores on in-clinic executive function and spatial memory assessments from about 200 people with FTD correlated with digital tasks taken on the ALLFTD mobile app (Jun 2022 conference coverage). At CTAD, he showed the same correlations with scores from almost 300 people.

Staffaroni further showed that digital cognitive scores tracked with brain atrophy. Poor performance on the smartphone executive function or memory tasks correlated with smaller frontoparietal/subcortical or hippocampal volumes, respectively, hinting that these digital tasks reflect changes in the brain areas that control each aspect of cognition.

Way of the Future

Knowing that remote and on-site cognitive tests are equally informative is crucial as clinical trials move toward decentralized designs. For example, TRAILBLAZER-ALZ3, a Phase 3 trial testing donanemab in cognitively normal older adults with brain amyloid, is using tests administered by video call as primary and secondary endpoints (Jul 2021 news; Nov 2021 conference news). Langbaum told Alzforum that, by showing that cognitive tests are equivalent when delivered from home, remote assessments can be used in TRAILBLAZER-ALZ3 and satisfy FDA requirements.

Other trials are also taking a decentralized approach. The latest iteration of the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative, ADNI4, will use online recruitment and remote blood biomarker screening to enroll participants (Oct 2022 news). So, too, will AlzMatch, a study determining if a blood sample collected at a local laboratory can help speed AD trial recruitment.

In her CTAD poster, Sarah Walter of the University of Southern California, Los Angeles, described an ongoing AlzMatch pilot study. She and colleagues asked 300 people enrolled in the Alzheimer Prevention Trials (APT) webstudy, an online registry of cognitively normal adults ages 50 to 85, to go to their local Quest Diagnostics for a blood draw. Samples are sent to C2N Diagnostics in St. Louis to measure their plasma Aβ42/40 concentration. Scientists at USC’s Alzheimer’s Therapeutics Research Institute (ATRI) then run each person’s biomarker result through an algorithm they developed to determine eligibility for further screening. ATRI researchers call each participant to tell them their result and whether they are eligible for a trial, then connect those interested in participating with a nearby clinical trial site.

So far, 142 participants have agreed to get their blood drawn, 68 went to have it done, and 22 have biomarker results from C2N. ATRI researchers are now referring the latter to research centers.

Walter said 47 percent of the participants responded to the invitation with similar response across demographic groups, i.e. age, ethnicity, race, and years of education. “By making research accessible in local communities, we hope to expand access to people who have a hard time traveling to academic centers,” Walter wrote to Alzforum. In toto, she and her team hope to enroll 5,000 people into this study. —Chelsea Weidman Burke

The first human trial of a gene therapy to counter damage wrought by the ApoE4 protein had results presented at the Clinical Trials in Alzheimer’s Disease meeting, held November 29-December 2 in San Francisco. Five homozygous ApoE4 carriers in different stages of AD received a single dose of LX1001, a virus equipped with the gene for the protective ApoE2 allele. Three months later, its payload was found within the cerebrospinal fluid, where it held steady out to a year, according to Michael Kaplitt of Weill Cornell Medical College in New York. In three women who had 12-month follow-up data, CSF concentrations of Aβ42, phospho-tau, and total tau shrank over the course of the trial.

“Targeting ApoE is a long-sought treatment for AD,” commented Stephen Salloway of Brown University in Providence, Rhode Island. “It is encouraging that there is some evidence of activity of ApoE2 in the CSF in a very small AD sample.”

“There is significant debate on whether APOE should be upregulated or downregulated, with reports showing both protective and pathological roles of ApoE4,” commented Pierre Tariot of Banner Alzheimer’s Institute in Phoenix. “Clinical trials may help answer this critical question,” Tariot added (full comment below).

ApoE4 was pegged as an AD risk factor 30 years ago. Shortly thereafter, ApoE2 emerged as a protective factor, and other rare variants were subsequently reported (Research timeline, ApoE Mutations database). Three decades on, researchers are still exploring which potential mechanisms explain the apolipoprotein’s sway over AD (Li et al., 2020). A recent analysis found that carriers of two copies of ApoE2 enjoy exceptional protection from AD, while other studies have shown that a single copy of ApoE2 can counter the AD risk imparted by a co-inherited copy of ApoE4 (Aug 2019 conference news; Genin et al., 2011).

Viral delivery of ApoE2 reportedly quells amyloid accumulation in transgenic mouse models (Nov 2013 news; Hu et al., 2015; Zhao et al., 2016). Collectively, these findings serve as the rationale behind the strategy of delivering ApoE2 to the brains of ApoE4 carriers.

At CTAD, Kaplitt reported early findings from an ongoing dose-ranging Phase 1/2 trial of LX1001, an adeno-associated virus (AAV) that carries a copy of the human ApoE2 gene. Developed by Ronald Crystal and colleagues at Weill Cornell, the virus provoked widespread expression of ApoE2 in the cortices and hippocampi of primates following injection into the cisterna magna, a space near the cerebellum to which CSF from the ventricles drains (Rosenberg et al., 2018). Crystal then founded Lexeo Therapeutics to develop LX1001.

The open-label study is evaluating three sequentially higher doses of LX1001 among 15 enrolled homozygous ApoE4 carriers with mild cognitive impairment or mild to moderate AD. So far, only the lowest-dose group has completed the one-year trial. They were five women, including one with MCI and four with moderate AD. They received a single intrathecal injection of 1012 vector genomes of LX1001 via lateral C1/C2 puncture. In this procedure, a needle is inserted just below the ear, and, with guidance from a CT scan, advanced into the subarachnoid space nestled between the top two vertebrae in the neck. Safety was the primary endpoint; secondary endpoints included CSF measurement of ApoE2 and AD biomarkers.

Special Delivery. LX1001 was delivered into the central nervous system of participants via C1/C2 puncture, in which a needle is inserted below the ear and into the space between the top two cervical vertebrae. [Weill Cornell Medical College.]

Kaplitt reported that so far, no serious adverse events have occurred in the low-dose group, or in the mid-dose group, who recently received 3x1012 vector genomes of LX1001. Two women among the former group had a transient headache following injection of LX1001, a common side effect of intrathecal puncture.

Lo and behold, when four of the women returned for CSF sampling three months later, ApoE2 was detected in the CSF of all of them. Only three participants were able to return for CSF sampling at the one-year timepoint, Kaplitt said, as logistical hurdles posed by the pandemic prevented the other two from traveling. In the three who returned, the CSF ApoE2 concentration held steady out to 12 months. “This gives us direct evidence that the virus has been taken up and is working to produce ApoE2,” Kaplitt told the audience. “Whether or not it’s enough to be effective obviously remains to be seen.”

Kaplitt also reported AD biomarker findings for three of the participants. CSF Aβ42 trended down in two of them, by 24 and 33 percent between baseline and 12 months. Phospho-tau and total tau nudged downward in all three participants, dropping by 9 percent to 16 percent for phospho-tau, and by 4 percent to 22 percent for total tau. With so few people in the trial, the findings are not statistically significant.

Researchers were cautiously optimistic about these first findings. They noted a litany of questions that remain unanswered. “Trans-cisternal delivery of ApoE2 is an approach that is very early in development, with many challenges, such as how to ensure sufficient delivery and uptake into cells that matter to produce a clinical benefit, what stage of disease makes the most sense, and how to scale this treatment if it proves to be effective,” Salloway commented.

“It was gratifying to see the first data on this gene therapy approach,” commented Lawrence Honig of Columbia University in New York. Honig also pointed to unknowns. For one, it is unclear whether the brain itself expressed APOE2, let alone which cell types there (full comment below).

When Warren Hirst of Biogen posed a similar question at CTAD, Kaplitt said that he does not know the answer in humans. In primates, however, delivery of LX1001 via a similar route was shown to promote widespread expression in neurons and glial cells in the cortex and hippocampus.—Jessica Shugart

Of the four anti-amyloid antibodies that wipe out plaque, Lilly’s donanemab is the only one still in a pivotal Phase 3 trial. The field will have to wait until mid-2023 for those results, but in the meantime, researchers at the 15th Clinical Trials on Alzheimer’s Disease conference, held November 29 to December 2 in San Francisco and online, got a glimpse at fresh biomarker data. Stephen Salloway of Butler Hospital in Providence, Rhode Island, presented preliminary results from TRAILBLAZER-ALZ 4, a head-to-head comparison of donanemab and aducanumab’s plaque-clearing ability.

As expected based on earlier studies with both drugs, donanemab banished plaque more rapidly, mopping up four times as much as aducanumab did in the first six months of treatment. More than a third of people taking donanemab fell below the threshold for global amyloid positivity in this time frame.

Dawn Brooks, who leads global development of donanemab at Lilly, said the data support the idea that treatment with donanemab could be quite rapid. Once a person becomes amyloid-negative, Lilly stops dosing. Brooks believes this short course of administration will be attractive to patients, limiting the cost and burden of treatment.

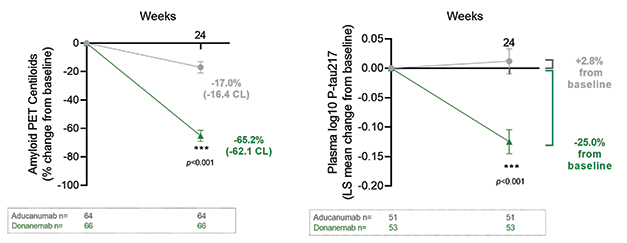

Fast Start. In six months of treatment, donanemab reached full dosing faster than aducanumab and cleared far more plaque (left). As a result, plasma p-tau217 dropped on donanemab as well (right). [Courtesy of Eli Lilly.]

In the earlier Phase 2 TRAILBLAZER study, plaque plummeted on donanemab, with 40 percent of people becoming amyloid-negative by six months, and 68 percent by 18 months. Downstream biomarkers such as p-tau217 and GFAP also fell (Mar 2021 conference news; Aug 2021conference news; Oct 2022 news). These data led Lilly to test donanemab directly against aducanumab, the only anti-amyloid antibody so far approved for clinical use by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (Jun 2021 news).

TRAILBLAZER-ALZ 4 is an open-label Phase 3 trial that enrolled 140 people with early symptomatic AD at 31 U.S. sites. Participants had an average age of 73 and MMSE of 24. Half of them received aducanumab, which was titrated according to the FDA label: 1 mg/kg for the first two months, then 3 mg/kg for two, and 6 mg/kg for two. Per this scheme, the full dose of 10 mg/kg was reached by seven months. Donanemab was titrated more quickly: 700 mg/month for the first three months, the full dose of 1,400 mg/month thereafter. The study’s primary outcome was amount of plaque removal at six months, before aducanumab had reached full dosing.

Lilly purchased aducanumab for this study. It did not include lecanemab in this comparison, partly because lecanemab is not approved, i.e., not as easily available, and partly—maybe, just maybe—because the difference in plaque removal speed might not have been as dramatic as with aducanumab.

When compared in this way, the difference in plaque removal between donanemab and aducanumab was stark. Participants on donanemab lost an average of 62 centiloids, those on aducanumab, 16. As a result, 38 percent of participants on donanemab dropped below the threshold for amyloid positivity, compared to 2 percent on aducanumab. Plasma p-tau217 tracked with plaque removal, falling 25 percent on donanemab at six months but staying flat on aducanumab.

The amount of ARIA-E was similar on each drug, around 22 percent, with the majority of those cases being asymptomatic. Salloway noted these data suggest that the speed of amyloid removal does not drive ARIA.

TRAILBLAZER-ALZ 4 collects no clinical data. This leaves unanswered the question of whether faster plaque removal is clinically better than slower removal. TRAILBLAZER 4 will continue to 18 months, allowing more analysis of how plaque removal changes over time as aducanumab dosing catches up.

Participants on donanemab will discontinue the drug once they become amyloid-negative, which Lilly defines as 11 centiloids. Some researchers have speculated that this short duration treatment may be necessary because donanemab triggers the generation of anti-drug antibodies that might dampen its efficacy over time. However, Brooks said Lilly has found no decrease in the amount of donanemab in the bloodstream over the course of 18 months of treatment, and has not needed to adjust antibody dosing within this time frame.

In donanemab's Phase 2, plaque burden took six months to creep back up over the 11 centiloids threshold after clearance. Brooks told Alzforum that p-tau217 stayed down for at least a year after dosing stopped. “We demonstrated that the change in a key downstream tau pathology biomarker was not dependent on continuing donanemab treatment, but rather was tied to the reduction in amyloid plaques,” she wrote to Alzforum.

Other scientists think a maintenance dose with an anti-amyloid antibody may be necessary. Lilly did not respond to a question regarding whether, or when, additional treatment with donanemab or another amyloid-removing drug might be needed as plaque reaccumulates.—Madolyn Bowman Rogers

No Available Comments

At first blush, recent Phase 3 trial results from the anti-amyloid antibodies gantenerumab and lecanemab seem to be a study in opposites, one negative and one positive. At the 15th Clinical Trials on Alzheimer’s Disease conference, held November 29 to December 2 in San Francisco, however, scientists said both programs together paint one and the same picture, of plaque needing to be completely cleared before the brain can—ever so slowly—respond.

This is because data from the two Phase 3 Graduate studies of Roche and Genentech’s gantenerumab showed that the antibody took but weak jabs at its target, clearing half as much plaque as expected during the trial’s more than two years of dosing. Far fewer participants became amyloid-negative as per PET than in the more fortunate Clarity trial of lecanemab. In Graduate, clinical measures all trended in the right direction, but the small changes fell short of statistical significance. Participants who dropped below the threshold for brain-wide amyloid positivity fared best.

It is unclear what went wrong with plaque clearance; Roche is currently analyzing pharmacokinetic data in search of answers. In the meantime, the company has halted its gantenerumab trials, though it continues to make the drug available to the Dominantly Inherited Alzheimer's Disease Trials Unit.

A Signal Is Not Enough. In the pooled Graduate data, gantenerumab nudged down decline about 8 percent, with nominal statistical significance. [Courtesy of Roche.]

Disappointment about the result was palpable everywhere at CTAD, as was praise for the quality of the clinical research program. “These were wonderful studies with extreme scientific rigor,” said Lefkos Middleton of Imperial College London. Randall Bateman of Washington University, St. Louis, who presented the results, emphasized the contribution even these negative findings can make. “This is an incredibly valuable dataset that will steer the field toward achieving larger-magnitude effects,” Bateman said in San Francisco. Roche also drew praise for sharing data publicly so soon—two weeks—after the data blind was broken.

Also at CTAD, plasma biomarker data from the negative Phase 3 trial of crenezumab were shown. As with previously reported cerebrospinal fluid markers, measures of tau pathology, inflammation, and neurodegeneration edged toward normal, but did not reach statistical significance. Clinical development of this drug is now over. [Correction posted January 19, 2023: According to Roche, evaluation of crenezumab in the API trial is concluding. However, according to AC Immune, the overall crenezumab development program has not been terminated].

Trends, But Nothing to Write Home About

Roche scientists selected gantenerumab’s Phase 3 dose based on open-label extension studies of their Scarlet Road and Marguerite Road trials. There, when given as a monthly subcutaneous injection of 1,200 mg, gantenerumab completely cleared plaque in half of participants at two years, and in 80 percent at three years (Dec 2017 conference news; Dec 2019 conference news).

The Graduate trials used a slightly lower dose, 1,020 mg given as two 510 mg injections every two weeks for 27 months. Doody noted that Roche switched to this split dosing to lower the volume that needed to be injected each time, and to make the shots less uncomfortable for patients. Subcutaneous antibody is delivered via syringe, usually into the abdomen, and can cause local reactions such as redness and swelling. In a poster at CTAD, Beate Bittner at Roche reported that participants found the pain from SC injections tolerable, fading within five minutes. Some OLE participants also received split doses, and PK analysis prior to Graduate had shown that it produced the same gantenerumab plasma levels the larger volumes did, Doody said.

Participants were titrated up to this level over nine months, meaning they got the target dose for 18 months, the same duration as the lecanemab Clarity trial.

The two trials, which ran from 2018 to 2022, enrolled 1,965 people from 30 countries, half of whom received gantenerumab. Participants were an average of 72 years old, with about 17 percent Hispanic or Latino, 12 percent Asian, and 3 percent American Indian or Alaska Native. Just over half the cohort, 55 percent, was diagnosed with mild cognitive impairment at baseline; the rest had mild dementia. The global CDR scores were slightly imbalanced, with three-fourths of people in the placebo groups having a CDR of 0.5, compared to two-thirds of people on gantenerumab. The remainder of both groups were more impaired, with a CDR of 1. Some researchers at CTAD wondered whether the greater impairment in the treatment group might have affected the results. Even if it did, the small difference is unlikely to explain why gantenerumab fell so far short of expectations, Doody told Alzforum.

As shown in the topline results, gantenerumab failed to slow decline on the primary outcome measure, the CDR-SB (Nov 2022 news). Treatment and placebo groups did diverge slightly, with people on gantenerumab posting a 0.31 and 0.19 point better score than those on placebo in Graduate 1 and 2, respectively, but this was statistically insignificant. In a prespecified pooled analysis, people on gantenerumab did 0.26 points better than those on placebo overall. This represented an 8 percent slowing of decline, which was nominally significant at p=0.04.

Results on secondary endpoints were similar, with trends favoring drug. Gantenerumab held back decline by about 14 percent on the ADAS-Cog13, 12 percent on the Functional Activities Questionnaire, and 9 percent on the ADCS Activities of Daily Living. None of this was statistically significant, though the ADAS-Cog13 and FAQ came close, averaging p=0.04.

Too Little Too Late. In Graduate 1 (left) and 2 (right), gantenerumab (blue) cleared plaque half as fast as projected over two years of treatment. [Courtesy of Roche.]

Weak Effect on Underlying Pathology What about amyloid removal? In the amyloid PET substudy of 383 people, gantenerumab cut plaque by about 23 centiloids after one year, and 53 centiloids after two years. Based on the prior OLE data, Roche scientists had expected reductions of 42 and 71 centiloids at one and two years, respectively. As a consequence, only 27 percent of people taking gantenerumab became amyloid-negative by two years, in contrast to half of people in the OLE, and two-thirds of people in the positive Clarity trial of lecanemab.

To explore whether plaque clearance affected the results, researchers compared CDR-SB scores in people who dropped below the positivity threshold of 24 centiloids and those who did not. The latter slipped three points on the CDR-SB over the course of the trial, identical to the placebo group, while the former slid two points, a third less decline. The results from this exploratory post hoc analysis add to the field’s growing sense that complete plaque clearance is key for realizing a cognitive benefit.

Clearance Matters. When participants were stratified by how much of their amyloid was removed, those with complete plaque clearance (blue) notched a cognitive benefit, unlike those without (green). Placebo group in gray. [Courtesy of Roche.]

The brain edema known as ARIA-E showed up as expected, in 22 percent of participants. This puts gantenerumab between aducanumab’s 33 percent and lecanemab’s 12 percent for this side effect. Five percent of people on gantenerumab developed symptoms from ARIA; 1 percent had serious symptoms. As with other anti-amyloid antibodies, ARIA-E was worse in APOE4 carriers, who made up two-thirds of the cohort. It occurred in 48 percent of E4 homozygotes, 24 percent of heterozygotes, and 12 percent of noncarriers.

Pierre Tariot of the Banner Alzheimer Institute in Phoenix asked why ARIA rates were similar to those in previous gantenerumab trials, even though amyloid removal was lower. Bateman noted that ARIA rose toward the end of the trial, when plaque removal sped up.

Cerebrospinal fluid biomarkers changed in the expected direction on gantenerumab. P-tau181 dropped by 24 percent; total tau, 18 percent. Neurogranin, which reflects synaptic loss, fell by 22 percent. All markers stayed relatively flat in the placebo group, and the differences were statistically significant. As with other anti-amyloid antibodies, the neurodegeneration marker NfL continued to rise on gantenerumab, but more slowly, by 11 percent rather than the 20 percent seen in the placebo group.

Two Decades of Development. The Graduate studies grew out of years of experiments to refine the antibody’s dosing and administration. [Courtesy of Roche.]

What to Make of It All?

Scientists at CTAD debated whether the result reflects a problem with how much gantenerumab was given, how it was given, or how the antibody was formulated. Robert Vassar of Northwestern University, Chicago, asked whether the subcutaneous administration was as reliable as intravenous dosing, which other antibodies still use. Most companies in the field are attempting to move to injection under the skin—is this a setback that should give them pause?

Doody said the company’s prior studies indicated that gantenerumab did reach adequate exposure via this route. At CTAD, Bittner presented pharmacokinetic analyses showing similar plasma concentrations of gantenerumab after IV or SC administration. All gantenerumab dosing has been subcutaneous since 2008, inspiring other anti-amyloid antibody programs to follow in hopes of lowering cost, relying less on infusion centers, and making the whole procedure more convenient for patients. In a Roche study of at-home administration, caregivers were able to dose patients using an auto-injector; 93 percent of caregivers felt confident doing so.

Others thought the antibody itself may have lost potency since earlier trials. Robert Przybelski of the University of Wisconsin, Madison, previously worked for Baxter Healthcare Corporation. Przybelski noted that when biologics drug production is scaled up for large, global trials, changes in the manufacturing methodology can reduce its effectiveness. Monoclonal antibodies are produced by cell lines grown in large bioreactors, and are harvested and purified in batches. Przybelski asked whether logs of batch activity testing might be consulted to probe for differences.

Doody acknowledged that Roche changed the cell line it used when production scaled up for Phase 3. This drew little notice at the time, but now has raised eyebrows as a possible culprit. Roche is looking into whether changes in formulation or production had an effect, Doody said.

Stephen Salloway of Butler Hospital in Providence, Rhode Island, brought up another angle, pointing out that the Graduate and Clarity populations were not the same. The Graduate participants started out with more amyloid, averaging 95 centiloids at baseline rather than 76. The population was also more impaired, with an average MMSE of 23 and CDR-SB of 3.7, and with 45 percent of participants having mild dementia. For lecanemab's Clarity trial, these numbers were 26, 3.2, and 38 percent, respectively. Would an earlier-stage population have gained more from treatment? Supporting this, a prespecified analysis by disease stage indicated that participants with MCI fared better on gantenerumab than those with mild dementia, losing 0.20 fewer points on the CDR-SB.

Given the trends in the outcome data all pointing in the same direction, David Morgan of Michigan State University, Grand Rapids, speculated that a longer trial might yet have demonstrated a benefit. Christopher van Dyck of Yale School of Medicine in New Haven, Connecticut, suggested exploring higher doses or faster titration.

Doody grasped at no straws, however. Although the Graduate results were disappointing, she said, they were very clear. Efficacy was insufficient. As a result, she said, Roche has halted its OLE studies of gantenerumab, as well as the at-home administration study. Ditto for the Skyline secondary prevention trial (Mar 2022 news). This latter news sparked dismay in the audience. Suzanne Hendrix of Pentara Corporation, Salt Lake City, questioned this decision, given the apparent higher benefits at earlier disease stages. So did others. Alas, Doody said the negative Graduate findings had shifted the risk/benefit ratio of gantenerumab.

While Graduate was still ongoing, the Dominantly Inherited Alzheimer Network had chosen gantenerumab for a primary prevention trial. This trial has been engaging mutation carriers older than 18 in a cognitive run-in phase to gather biomarker data and improve statistical power before a drug had even been chosen. DIAN-TU discussed Graduate's topline results with its participating families, who decided they wanted to continue with the plan. Indeed, the primary prevention trial consented its first patient during the CTAD conference, Eric McDade of Washington University, St. Louis, told Alzforum. After the conference, however, DIAN-TU leaders made the decision to switch from gantenerumab, because there might not be enough antibody available to finish the trial. This trial will give a study drug for four years during its blinded phase and then for four more years in open-label extension. DIAN-TU will continue to enroll participants in the cognitive run-in while choosing a new drug (see announcement).

DIAN-TU is still dosing with gantenerumab in the OLE of its secondary prevention study (Apr 2020 conference news; Jun 2021 news). In this program, DIAN uses a three times higher dose than Graduate did, spread out over several injections. Doody noted that the higher dosing might overcome any loss of potency in the antibody. Roche is currently making gantenerumab available to this OLE, and is in discussions with DIAN-TU regarding next steps.

Doody emphasized that despite the negative results for this formulation of gantenerumab, Roche is pursuing alternatives. One is its brain-shuttle delivery program. Both arms of this antibody contain the amyloid-binding portion of gantenerumab and it is attached to the transferrin receptor shuttle molecule by a chain. The receptor ferries the antibody into the brain, achieving 10- to 20-fold higher brain concentration than peripheral administration (Mar 2021 conference news; Dec 2021 conference news). Currently in a Phase 1b/2a study, the shuttle antibody, dubbed trontinemab, is being developed separately from gantenerumab, and may well have different effects due to its broader distribution through the brain, Doody noted. “The field needs ways to get more antibody into the brain,” she told Alzforum.

Farewell Crenezumab

Crenezumab is IgG4 antibody that targets Aβ oligomers and monomers but does not clear plaque. It missed primary and secondary endpoints in the API Colombian prevention study, though trends on nearly all endpoints favored drug (Jun 2022 news; Aug 2022 conference news). Roche currently has no plans for testing it further.

In San Francisco, Eric Reiman of Banner presented plasma data. It was collected from all participants over several years, but analyzed only recently in one batch at a single lab. At baseline, cognitively unimpaired carriers of the E280A Paisa mutation in presenilin 1 had higher p-tau181 and p-tau217 than the 83 noncarriers, as expected. Their plasma Aβ42/40 ratio was higher than in noncarriers, reflecting overproduction of the toxic form of Aβ. In addition, carriers had more of the inflammation marker GFAP and the neurodegeneration marker NfL than did noncarriers.

Over time, all markers except Aβ42/40 rose in the 84 carriers on placebo. The inflammatory marker sTREM2, while not elevated at baseline, also rose in carriers over time. Meanwhile, the Aβ ratio dropped, indicating Aβ42 sequestration into plaques. In the 85 mutation carriers taking crenezumab, plasma Aβ42 rose significantly, likely as a result of crenezumab binding it and slowing its clearance. All other markers trended back toward normal, but the changes were not statistically significant. These markers are measured in pg/mL.

Separate subgroup analyses of those carriers who were still amyloid negative versus already amyloid-positive at baseline are underway, Reiman said. In the meantime, API is closing out the study, finishing final visits with participants now. Other drugs will be evaluated in this population in the future, Reiman noted.—Madolyn Bowman Rogers

No Available Comments

A growing body of research discusses lifestyle factors as targets for dementia prevention, with the potential to bolster health and hold off cognitive decline. Trouble is, trials that broadly address health and fitness have met with mixed success. How to make lifestyle interventions work? At the 15th Clinical Trials on Alzheimer’s Disease conference, held November 29 to December 2 in San Francisco and online, both Kristine Yaffe of the University of California, San Francisco, and Miia Kivipelto of the Karolinska Institute in Stockholm suggested nondrug interventions be tailored to the individual, and paired with drugs.

Yaffe presented the Systematic Multi-domain Alzheimer’s Risk Reduction Trial (Smarrt), a pilot prevention study investigating whether personalizing lifestyle prescriptions improves brain health. At CTAD, she reported top-line results showing that targeting specific areas where a given individual needed the most help—for example, sleep, diabetes management, social contact—boosted cognitive scores more than was seen in previous multi-domain trials. This pilot paves the way for larger trials investigating the approach, Yaffe said. The positive findings add to evidence that prevention approaches can work to keep the brain healthy with age.

“Multi-domain interventions can be feasible and effective,” Kivipelto said in a keynote talk at CTAD, adding, “It is never too early, and never too late, to start.” Kivipelto and Yaffe both said the next step will be to combine such interventions with drugs to achieve larger effects.