Axons or Bust: To Reach Neuron Extremities, RNAs Hitch a Ride on Lysosomes

Quick Links

To allow for the local translation of proteins that suit the ever-changing needs of the axon, neurons must ship transcripts from the soma to their outermost reaches. For thousands of these mRNAs, hitchhiking is their predominant mode of transport. This is according to a study led by Juan Bonifacino at the National Institutes of Health in Bethesda, Maryland, which found that traveling lysosomes give mRNAs a ride along microtubule highways. As described April 10 in Nature Neuroscience, without proteins that tether lysosomes to kinesin motors, thousands of transcripts failed to reach their destination. Among the marooned were those encoding ribosomal subunits and mitochondrial proteins. Mitochondrial biogenesis and respiration faltered, ultimately leading to misshapen, degenerating axons akin to those seen in neurodegenerative diseases. The findings uncover a fundamental biological mechanism that keeps axons flush with enough proteins and energy to support neurotransmission.

- Disabling lysosomal trafficking depletes axonal RNAs.

- Ribosomal and mitochondrial transcription stalls.

- Without local protein translation, mitochondria falter.

“These findings underscore the importance of understanding the basic mechanism of mRNA transport and localization, and offer insights into potential mechanisms underlying axon degeneration and neurodegeneration,” commented Eran Perlson of Tel Aviv University. He thinks it could lead to new avenues for therapeutic exploration (comment below).

All A-BORC! Along with ARL8 and PLEKHM2, the BORC complex forms a bridge between lysosomes and kinesin-1, which transports the vesicles along microtubules into axons. [Courtesy of de Pace et al., Nature Neuroscience, 2024.]

Axons are dynamic hubs of synaptic activity and protein turnover that require vast amounts of energy. How does the mRNA make it that far? Previously, researchers reported that RNA granules, which are membraneless organelles comprising a mix of RNA and RNA-binding proteins, travel from the soma into axons by tethering themselves to lysosomes via the annexin-11 protein (Liao et al., 2019). Lysosomes and related vesicles travel in axons bidirectionally, using kinesin motors to move out toward axonal terminals, and dynein on the return trip.

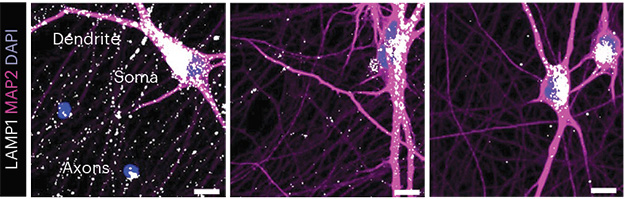

Co-first authors Raffaella De Pace and Saikat Ghosh and colleagues wanted to investigate how this lysosomal schlepping influences the axonal RNA repertoire, and how that might support axon biology. To do this without disabling all modes of transport, the researchers knocked out BLOC-one-related complex (BORC), which, together with the small GTPase ARL8, and the adaptor protein PLEKHM2, couples lysosomes to kinesins 1 and 3. BORC is an octameric complex, and the researchers used CRISPR to generate human iPSC-derived neurons lacking either BORCS5 or BORCS8 subunits, each needed for the tie to lysosomes. When i3 neurons derived from iPSCs lacked either subunit, they appeared to mature normally relative to their BORC-replete counterparts, sprouting axons. However, a closer look revealed profound differences. While lysosomes were broadly distributed in the soma, dendrites, and axons of wild-type neurons, i3s lacking a BORC subunit housed few, if any, lysosomes in their axons (image below).

No Ride for Lysosomes. In wild-type i3 neurons (left), LAMP1+ lysosomes (white) are found in dendrites, soma, and axons. Without BORC5 (middle) or BORC7 (right), few lysosomes travel into axons. [Courtesy of de Pace et al., Nature Neuroscience, 2024.]

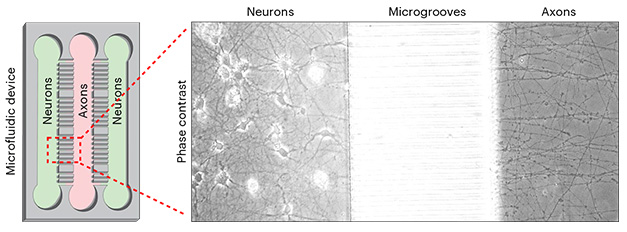

How would this shutdown influence the repertoire of transcripts found there? To isolate axonal transcripts, the researchers grew iPSCs in a microfluidic device in which the cells are plated on either side of a series of microgrooves that flow into a central chamber. As the iPSCs develop into neurons, only axons are long and thin enough to traverse the microgrooves into the central chamber, where the researchers harvested them for analysis (image below). In this way, researchers could isolate and sequence RNA from pure axons, and compare it to the transcripts found within the side chambers that housed all neuronal parts.

Get into the Groove. Neurons were grown in two chambers of a microfluidic device, positioned on either side of microgrooves (left). [Courtesy of de Pace et al., Nature Neuroscience, 2024.]

The upshot? BORC deficiency profoundly affected the axonal transcriptome. Focusing on wild-type neurons first, the researchers found that axons were steeped in transcripts encoding ribosomal RNAs, ribosomal subunits, and mitochondrial proteins involved in oxidative phosphorylation. In BORC-KO neurons, the axonal, but not the soma, transcriptome was dramatically altered. Ribosomal RNAs plummeted, as did more than 2,000 protein-coding transcripts. Notably, many of the depleted axonal transcripts have been implicated in neurodegenerative diseases, including Parkinson’s, Huntington’s, Alzheimer’s, and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis.

While BORC-less axons took an RNA loss, their neuronal cell bodies saw an increase in more than 3,000 transcripts relative to wild-type neurons. These hailed from numerous biological pathways and corresponded to cell body, not axonal transcripts. RNAs encoding lysosomal proteins were among those most increased in BORC KO neurons, suggesting neurons may have been attempting to compensate for the loss of lysosomes in the axons, the authors proposed.

These shifts in the axonal transcriptome exacted a steep toll: for one, a dearth of functional ribosomes, which, in turn, sapped mitochondrial protein translation. In particular, components of the mitochondrial membrane electron transport chain were reduced. Loss of these proton-pumping proteins led to a dip in the mitochondrial membrane potential, stressing the organelles. Fewer mitochondria inhabited BORC KO neurons, and those that persisted were smaller and misshapen (image below). Their cristae—the membrane folds that provide the surface area for energy-producing oxidative phosphorylation—were few and irregularly spaced.

Mitochondrial Meltdown. Compared to the large, intact mitochondria found in wild-type axons (left), those in BORCS7 KO axons were small, with deformed cristae (right). [Courtesy of de Pace et al., Nature Neuroscience, 2024.]

Swirly Swellings. Wild-type axons (top) are uniform and thin, with occasional mitochondria (green). By contrast, BORCS5 KO axons have swellings, which sometimes include microtubule swirls and mitochondria (green). [Courtesy of de Pace et al., Nature Neuroscience, 2024.]

All this mitochondrial mayhem instigated mitophagy, a form of autophagy that serves to rid the cell of dysfunctional mitochondria. As evidence of this, the researchers spotted axonal vesicles expressing the autophagosomal marker LC3B, some of which contained the remnants of mitochondria. Both these autophagosomes and failing mitochondria accumulated within numerous axonal swellings. The lack of lysosomes entering BORC-KO axons meant that autophagosomes had no digestive vesicles to fuse with, resulting in a glut of constipated autophagosomes within the axon.

In addition to festering autophagosomes, axonal swellings were chock-full of the microtubule-binding protein tau, as well as tangled up bits of microtubules called swirls, a common morphological feature of degenerating axons (image at right). This axonal destruction ultimately spelled doom for BORC-KO neurons, which died long before their wild-type counterparts did.

The findings cast lysosomal hitchhiking as a bona fide, and crucial, mode of RNA transport into axons, and offer mechanistic insight into rare neurodevelopmental and neurodegenerative disorders that occur among carriers of BORC mutations (de Pace et al., 2023). Furthermore, because endolysosomal dysfunction factors into several neurodegenerative diseases, the study suggests that poor axonal delivery of RNAs may contribute to axonal degeneration more broadly, de Pace told Alzforum.

Wim Annaert of KU Leuven in Belgium agreed that the findings have broad implications for neurodegenerative disease. “This study may contribute to an alternative understanding of mitochondrial dysfunction in neurodegenerative diseases, including Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s,” he wrote. “This paper provides a mechanism by which mitochondrial defects can clearly occur downstream of lysosomal dyshomeostasis, propagating defects to other organelles and leading ultimately to neuronal degeneration.”—Jessica Shugart

References

Paper Citations

- Liao YC, Fernandopulle MS, Wang G, Choi H, Hao L, Drerup CM, Patel R, Qamar S, Nixon-Abell J, Shen Y, Meadows W, Vendruscolo M, Knowles TP, Nelson M, Czekalska MA, Musteikyte G, Gachechiladze MA, Stephens CA, Pasolli HA, Forrest LR, St George-Hyslop P, Lippincott-Schwartz J, Ward ME. RNA Granules Hitchhike on Lysosomes for Long-Distance Transport, Using Annexin A11 as a Molecular Tether. Cell. 2019 Sep 19;179(1):147-164.e20. PubMed.

- De Pace R, Maroofian R, Paimboeuf A, Zamani M, Zaki MS, Sadeghian S, Azizimalamiri R, Galehdari H, Zeighami J, Williamson CD, Fleming E, Zhou D, Gannon JL, Thiffault I, Roze E, Suri M, Zifarelli G, Bauer P, Houlden H, Severino M, Patten SA, Farrow E, Bonifacino JS. Biallelic BORCS8 variants cause an infantile-onset neurodegenerative disorder with altered lysosome dynamics. Brain. 2024 May 3;147(5):1751-1767. PubMed.

Further Reading

No Available Further Reading

Primary Papers

- De Pace R, Ghosh S, Ryan VH, Sohn M, Jarnik M, Rezvan Sangsari P, Morgan NY, Dale RK, Ward ME, Bonifacino JS. Messenger RNA transport on lysosomal vesicles maintains axonal mitochondrial homeostasis and prevents axonal degeneration. Nat Neurosci. 2024 Jun;27(6):1087-1102. Epub 2024 Apr 10 PubMed.

Annotate

To make an annotation you must Login or Register.

Comments

No Available Comments

Make a Comment

To make a comment you must login or register.