Reconceptualizing the BBB: Is It Time to Swap ‘Barrier’ for ‘Border'?

Quick Links

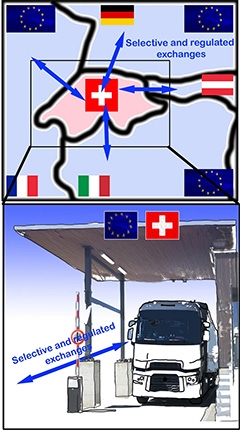

The image of the “blood-brain barrier” as a static wall that shields the brain from the rest of the body is crumbling. A group of scientists argue, in a review published in Fluids and Barriers of the CNS earlier this year, that it’s time to adopt a more apt metaphor. Jan Pieter Konsman and Jerome Badaut of the University of Bordeaux, France; Jean-François Ghersi-Egea of Lyon Neurosciences Research Center, France; and Robert Thorne of Denali Therapeutics in South San Francisco, likened the blood-brain interface to a border crossing between countries, whereby people, goods, and taxes are exchanged to serve the needs of the countries on either side. Just as such borders adapt to changing times, the “blood-brain border” adapts in both time and space, adjusting its list of “approved” molecules depending on age and a healthy or diseased local environment. This is a better metaphor than a purely obstructive barrier standing in the way of CNS-targeted therapeutics.

- Scientists suggest adopting the term “blood-brain border” to reflect the complexity and dynamism of the interface.

- Rather than a purely obstructive barrier, the BBB is more like a highly selective geopolitical border crossing.

- The molecules allowed across change with age and brain region, and shift depending on need.

“The term border does more justice to the flexibility observed in the (patho)physiology of the blood–brain interface, while avoiding the negative connotation of disruption or rupture,” the authors wrote. They see the new term as a way to “stimulate new drug approaches to modulate the properties of CNS endothelial and epithelial layers, or take advantage of endogenous systems, rather than finding ways to ‘break the barrier’ to facilitate drug delivery to the CNS.”

Bustling Border. In this schematic of the border between Switzerland and European Union nations, the exchange of people, taxes, and goods at crossing points adapts as relationships between countries evolve. Similarly, the blood-brain border shifts in time and space. [Courtesy of Badaut et al., Fluids and Barriers of the CNS, 2024.]

Scientists who study the intricacies of the brain’s extensive vasculature have long known that selective molecules traverse it via different mechanisms. Still, many emphasize the restrictiveness of the BBB, focusing on the barrier properties of the tight junctions that physically seal spaces between endothelial cells lining vessels. Yet squeezing across these crevices is not the way most molecules—particularly larger ones—manage to cross. Instead, a variety of selective paths, such as solute channels, receptor-mediated transcytosis systems, and vesicular trafficking are at work across the vasculature, the scientists emphasized.

Jürgen Götz of the University of Queensland in Brisbane, Australia, welcomed the change in terminology. With his work using ultrasound to temporarily open the BBB, Götz acknowledged that he initially viewed it as a barrier to be breached (Mar 2015 news). Yet further studies have continued to unveil the nuanced mechanisms underlying changes in so-called BBB “permeability,” including those that change with age and disease. Götz noted a study led by Tony Wyss-Coray of Stanford University. It showed that, at least in mice, while plasma proteins readily permeate the healthy brain parenchyma, their uptake flags in the aged brain due to a shift from ligand-specific, receptor-mediated modes of transport, to nonspecific caveolar transcytosis (Jul 2020 news).

Operative transport mechanisms vary substantially from segment to segment across the cerebral circulation, noted Costantino Iadecola of Weill Cornell Medical College in New York, who was not involved in the review. For example, at the capillary level, the BBB is dominated by solute transporter carriers, while larger vessels favor vesicular transport mechanisms, he said. “There is this zonal diversity to the interface with the blood, and that’s only one of the interfaces in the brain.”

Intricate Interfaces. In addition to the blood-brain border (top right), the brain’s other interfaces include the inner blood-CSF border within the choroid plexus (bottom left) and the outer blood-CSF border within the leptomeninges (bottom right). Each border has distinct cellular, molecular and structural attributes. [Courtesy of Badaut et al., Fluids and Barriers of the CNS, 2024.]

Other interfaces include the blood-CSF borders, such as the one between the blood and the choroid plexus, as well as between the blood and leptomeningeal spaces on the surface of the brain (image above). Denali’s Thorne takes the view that it is at these CSF borders, rather than capillary blood-brain interfaces, where minuscule amounts of therapeutic monoclonal antibodies tend to cross. After traversing the fenestrated blood vessels that predominate within the choroid plexus, these large macromolecules get snagged in the surrounding stroma before some of them cross into the CSF. There, they travel across the brain surface and into perivascular spaces around large caliber vessels that traverse the leptomeninges. These spaces are also where cerebral amyloid angiopathy occurs. Thorne and other scientists think that when anti-Aβ antibodies latch onto this vascular amyloid, the inflammatory consequences that manifest as ARIA ensue.

To avoid this risk and to improve delivery into the brain, some companies are taking advantage of the transferrin receptor to whisk monoclonal antibodies across. Notably, TfR expression is highest within the microvasculature, rather than at larger vessels where CAA accumulates. An appreciation for the diversity of transport mechanisms at work across the cerebrovasculature may thus allow scientists to side-step damaging responses and deliver their drugs more broadly throughout the brain parenchyma, as described in the previous story (Oct 2024 news).

The concept of a blood-brain border matches the military-inspired words used to describe immune cells that “patrol” these borders, and “infiltrate” the brain when recruited by cells on the other side. For example, the role of T cells in exacerbating neurodegenerative disease has become increasingly appreciated in recent years (Mar 2023 news). Moreover, Iadecola and other scientists have found that macrophages residing in the perivascular space—aptly named “border-associated macrophages” (BAMs)—play an important part in surveilling border crossings, but are capable of unleashing a deadly inflammatory cascade of free radicals that exacerbates CAA and may even cause ARIA (Apr 2023 conference news; Aug 2024 conference news).

“The roles that these brain macrophages play, in addition to their strategic positioning in what can be considered to be defensive buffer zones along blood–brain interfaces, fully justifies the name border-associated macrophages, and further encourages us to consider these interfaces as biological borders,” the authors wrote.

Iadecola applauded the authors for starting this discussion, and agreed that “border” is a more appropriate term than “barrier.” However, he added that “border” barely scratches the surface of the complexities of the brain’s diverse vasculature. “With so many different interfaces and different types of borders within them, maybe we should be splitting instead of lumping,” he said. Still, he said that the brain’s myriad interfaces do serve a common purpose, that is, to maintain homeostasis, whether by delivering nutrients, clearing junk, healing a wound, or quashing an infection.—Jessica Shugart

References

News Citations

- Stop, Hey, What’s That Sound? ... Amyloid Is Going Down?

- Blood-Brain Barrier Surprise: Proteins Flood into Young Brain

- Tweaked, Aβ-Antibodies Cross Blood-Brain ‘Border’ (Bye-Bye, Barrier?)

- Neurodegeneration—It’s Not the Tangles, It’s the T Cells

- Macrophages Blamed for Vascular Trouble in ApoE4 Carriers

- Implicated in ARIA: Perivascular Macrophages and Microglia

Further Reading

No Available Further Reading

Primary Papers

- Badaut J, Ghersi-Egea JF, Thorne RG, Konsman JP. Blood-brain borders: a proposal to address limitations of historical blood-brain barrier terminology. Fluids Barriers CNS. 2024 Jan 5;21(1):3. PubMed.

Annotate

To make an annotation you must Login or Register.

Comments

No Available Comments

Make a Comment

To make a comment you must login or register.