Protective ApoE Variant Quells Interferon Responses in Tauopathy

Quick Links

After the ApoE3-R136S “Christchurch” variant had held off the inevitable onslaught of Alzheimer’s disease by three decades in a woman with a pathogenic familial mutation, her brain was riddled with amyloid plaques but mostly free of neurofibrillary tangles. How did a point mutation in ApoE put a wrench in the AD cascade? According to a preprint posted April 28 on bioRxiv, it may calm an inflammatory wave. Scientists led by Li Gan, Weill Cornell Medical College in New York, report that in mice carrying the variant, microglia toned down their interferon responses, in part by not activating cGAS-STING, a cytosolic DNA sensor that can get tripped when nucleic acids leak from damaged organelles. This restraint spared synapses and prevented memory loss. Similarly, a cGAS inhibitor also protected synapses and downregulated the interferon response.

- In tauopathy mice, the ApoE3-R136S variant safeguards synapses and memory.

- It quells the microglial interferon response instigated by cGAS-STING pathway.

- A cGAS inhibitor similarly shielded synapses and squelched the interferon cascade.

Since the discovery that two copies of ApoE3-R136S (formally R154S) seemed to sever the tie between amyloid and tau pathologies, scientists have been digging for the mechanisms (Nov 2019 news; Sep 2022 conference news). Last year saw a report that the variant reduced seeding and toxicity of tau fibrils in mouse models of amyloidosis and tauopathy (Dec 2023 news).

For the current study, co-first authors Sarah Naguib, Eileen Torres, and Chloe Lopez-Lee and colleagues used CRISPR to replace both copies of the mouse ApoE gene with human ApoE3, or ApoE3-R136S. They then crossed these with PS19 mice, which express the FTD-causing P301S mutation in tau.

In tests of spatial learning and memory, 9-month-old male, but not female, ApoE3-PS19 mice were profoundly deficient compared to ApoE3 knock-ins on a wild-type background. The ApoE3-R136S staved off these memory problems, hence the scientists limited further analyses studies to males.

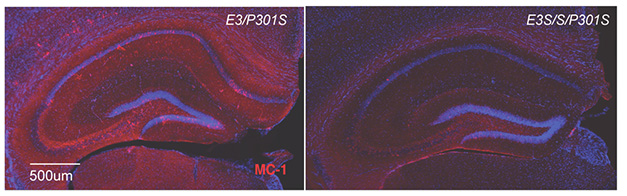

PS19 males expressing the Christchurch variant bore about half the tangle burden of their ApoE3 counterparts (image below). They also retained most of their synapses, while ApoE3-PS19 mice lost about a third. Despite these differences, microgliosis and astrogliosis unfolded similarly, regardless of which ApoE3 variant the mice expressed. Gan wondered if the type, rather than extent, of the glial response might help explain the variant’s protective effects.

Tone Down Tau. ApoE3-PS19 mice (left) had twice as much aggregated tau (red) in the hippocampus as did ApoE3- R136S-PS19 mice (right). [Courtesy of Naguib et al., bioRxiv, 2024.]

To probe cell responses, the researchers surveyed the transcriptomes of single nuclei from the hippocampi of 9- to 10-month-old PS19 males. They detected effects of the variant on gene expression across multiple cell types. Notably, in R136S homozygotes, microglia downregulated genes involved in the type I interferon response. These included many genes upstream of the cascade, such as cyclic GMP-AMP synthase, aka cGAS. Previously, Gan had reported that this cytosolic DNA sensor became activated when tau fibrils damaged mitochondria, leaking mtDNA into the cytosol (Apr 2022 conference news). Once riled, cGAS triggers the protein STING to oligomerize, tripping off the interferon cascade (reviewed in Decout et al., 2021). Naguib and colleagues found dense clusters of the activated STING in ApoE3/PS19 mice, but hardly any in PS19 mice expressing the protective variant.

Tau fibrils triggered an inflammatory interferon cascade in primary microglia cells from ApoE3, but not in microglia from ApoE3-R136S mice. What’s more, R136S microglia rapidly degraded internalized tau. Gan told Alzforum that preliminary work in her lab suggests that a cGAS inhibitor similarly sped up digestion of tau fibrils within microglia, but doesn’t rule out that the variant might also encourage the cells to internalize tau. The original case study of the protective variant revealed that the R136S variant binds poorly to heparin sulfate proteoglycans, which could free up the surface receptors to latch onto tau (Arboleda-Velasquez et al., 2019).

Would inhibiting cGAS imitate the variant? To find out, the scientists fed 6-month-old ApoE3-PS19 mice chow laced with TDI6570, a brain-penetrant cGAS inhibitor. By 9 months of age, untreated ApoE3-PS19 mice had one-third fewer synapses than ApoE3 non-tauopathy mice or ApoE3-PS19 mice that had been treated with the cGAS inhibitor. Furthermore, single-nuclei transcriptomics revealed more overlap in the effects of the inhibitor and ApoE3-R136S in the mice across multiple cell types than would be expected by chance, Gan said. In microglia, several immune and interferon genes were among those commonly downregulated by both.

The findings suggest that turning down the type I interferon response explains part of the protection afforded by ApoE3-R136S, implying that some of the benefits of this rare mutation might be attained pharmacologically, with a cGAS inhibitor.

Gan believes that in tauopathies, mitochondrial DNA in microglia is the chief activator of cGAS. However, neurons express small amounts of the synthase and sustain DNA damage in tauopathies; they might also set it off. Her lab is generating conditional cGAS knockout mice to learn if other cells are involved, as well.

How ApoE3-R136S keeps the brakes on cGAS is unclear. The benefits could stem from bolstering microglial clean-up of tau fibrils, or from the way microglia respond to the pathology, Gan said.

Yun Chen and David Holtzman of Washington University in St. Louis have also hypothesized that ApoE3-R136S increases uptake and processing of tau fibrils. “What still eludes the field is the protection mechanism of ApoE-Christchurch at the cellular level,” they wrote (comment below). They think it is possible that the cGAS-STING-IFN pathway is involved, but believe reduced neurodegeneration might also contribute.

Yann Le Guen of Stanford University in Palo Alto begged off commenting on Gan’s study before it undergoes peer review, but noted that small numbers of mice and statistical techniques used in some of the snRNA-Seq experiments render the conclusions uncertain. He considers it unlikely that impaired binding to HSPGs explains why Christchurch protects, since he identified another HSPG-binding-deficient form of ApoE3, R145C (formally R163C), which either had no impact, or increased the risk of AD among African Americans, depending on their ApoE genotype (Mar 2023 news). Further studies are needed to understand how the protective variant stems the tide of tauopathy, Le Guen suggested.

Gan views the discovery of the protective variant as “nature’s gift.” “It is a highly resilient modifier, and if we can harness that, it may give us some way to reduce tau toxicity,” she said.—Jessica Shugart

References

Mutations Citations

News Citations

- Can an ApoE Mutation Halt Alzheimer’s Disease?

- In Brain With Christchurch Mutation, More ApoE3 Means Fewer Tangles

- APOE Christchurch Variant Tames Tangles and Gliosis in Mice

- Just Like Viruses, Tau Can Unleash Interferons

- In People with African Ancestry, ApoE3 Variant Ups Alzheimer's Risk

Paper Citations

- Decout A, Katz JD, Venkatraman S, Ablasser A. The cGAS-STING pathway as a therapeutic target in inflammatory diseases. Nat Rev Immunol. 2021 Sep;21(9):548-569. Epub 2021 Apr 8 PubMed.

- Arboleda-Velasquez JF, Lopera F, O'Hare M, Delgado-Tirado S, Marino C, Chmielewska N, Saez-Torres KL, Amarnani D, Schultz AP, Sperling RA, Leyton-Cifuentes D, Chen K, Baena A, Aguillon D, Rios-Romenets S, Giraldo M, Guzmán-Vélez E, Norton DJ, Pardilla-Delgado E, Artola A, Sanchez JS, Acosta-Uribe J, Lalli M, Kosik KS, Huentelman MJ, Zetterberg H, Blennow K, Reiman RA, Luo J, Chen Y, Thiyyagura P, Su Y, Jun GR, Naymik M, Gai X, Bootwalla M, Ji J, Shen L, Miller JB, Kim LA, Tariot PN, Johnson KA, Reiman EM, Quiroz YT. Resistance to autosomal dominant Alzheimer's disease in an APOE3 Christchurch homozygote: a case report. Nat Med. 2019 Nov;25(11):1680-1683. Epub 2019 Nov 4 PubMed.

Further Reading

No Available Further Reading

Primary Papers

- Naguib S, Torres ER, Lopez-Lee C, Fan L, Bhagwat M, Norman K, Lee SI, Zhu J, Ye P, Wong MY, Patel T, Mok SA, Luo W, Sinha S, Zhao M, Gong S, Gan L. APOE3-R136S mutation confers resilience against tau pathology via cGAS-STING-IFN inhibition. bioRxiv. 2024 Apr 28; PubMed.

Annotate

To make an annotation you must Login or Register.

Comments

No Available Comments

Make a Comment

To make a comment you must login or register.