An Antimicrobial Approach to Treating Alzheimer’s?

Quick Links

Do periodontal bacteria cause some cases of Alzheimer’s disease? Scientists at one start-up think so, and their investors are putting their money where their mouths are, moving forward with clinical development of a bacterial protease inhibitor. In the January 23 Science Advances, Stephen Dominy and Casey Lynch of Cortexyme, Inc., South San Francisco, California, claim that the oral pathogen Porphyromonas gingivalis can move from the mouth into the brain, where it may instigate AD. People with Alzheimer’s disease have elevated levels of the bacterial protease gingipain in their brain tissue, they find. In mice, small-molecule gingipain inhibitors ameliorate infection, reduce Aβ42 peptide production and neuroinflammation, and protect neurons from gingipain toxicity. The company has completed Phase 1 clinical trials of their gingipain inhibitor COR388, and will run a Phase 2/3 study to determine if it can improve cognition in people with mild to moderate AD, Lynch told Alzforum.

- Traces of a gum bacteria are present in the brains of people with AD.

- It may initiate or aggravate AD pathology.

- Inhibitors of the bacterium’s proteases are in clinical trials.

Multiple studies confirm that older people with periodontal disease have an increased risk of Alzheimer’s and cognitive decline (Leira et al., 2017). While it’s unclear whether poor hygiene and gum disease lead to dementia, or vice versa, one hypothesis blames the association on P. gingivalis, a predominant cause of chronic gum inflammation.

P. gingivalis is not the only microbe implicated in AD. Others include spirochetes, Chlamydia pneumoniae, and herpes simplex virus (June 2018 news; June 2018 news). Nonetheless, mouse studies support the theory that this particular oral bacteria can travel to the brain, where infection triggers or exacerbates AD pathology by increasing Aβ production, amyloid deposition, tau phosphorylation, and neuroinflammation, resulting in hippocampal cell death and cognitive decline (Ilievski et al., 2018; Ishida et al., 2017).

In the new work, Dominy and Lynch claim that P. gingivalis infects the central nervous system. In postmortem samples of the middle temporal gyri from 100 adults, people with neuropathologically confirmed AD had two to three times more gingipain than did non-demented controls. The bacteria release these three related proteases to clear the way for its spread, and they destroy gum tissue in periodontal disease. In the AD samples, gingipains correlated with increasing tau and ubiquitin immunoreactivity, regardless of symptoms. Protease levels did not correlate with age, suggesting time alone did not explain the relationship, Lynch told Alzforum.

The researchers also spotted gingipain and bacterial DNA in the cortices of three AD brain samples and in six of seven non-demented controls, consistent with common P. gingivalis infection in older adults. To assess CNS infection in living people, they devised an assay to test for fragmented bacterial DNA in cerebrospinal fluid, and reported results in a small sample. Of 10 people clinically diagnosed with AD, seven tested positive, albeit at DNA levels down to a thousandth of those found in the mouth.

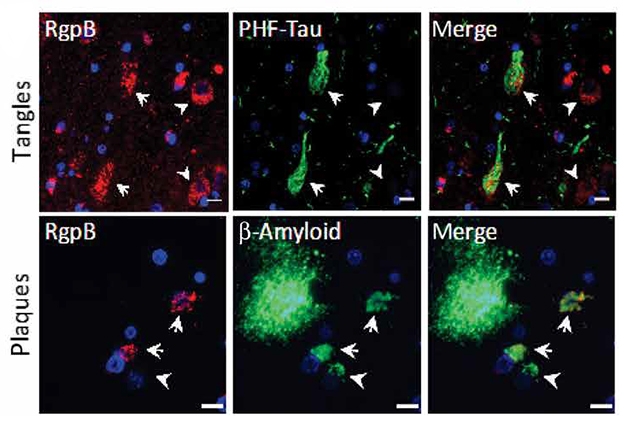

In the brain, the proteases appeared primarily in neurons, and some co-localized with phospho-tau and intraneural Aβ. The former could potentially contribute to tau pathology, the researchers believe, as gingipains cut up tau in P. gingivalis-infected SH-SY5Y cells. In vitro digestion of tau with gingipains revealed dozens of cleavage sites and fragments known to be increased in CSF in AD, or implicated in tangle formation. The interaction with Aβ is consistent with that peptide’s proposed antimicrobial function (May 2016 news; Spitzer et al., 2016).

Trouble Spots. The gingipain protease RgpB (red) co-localizes with tau-paired helical filaments (top) and intracellular Aβ (bottom) in the AD hippocampus. [From Dominy et al., 2019, Science Advances.]

Lynch and Dominy believe their data indicate that infection can precede and precipitate AD, but other researchers were not convinced. “What they’ve done is solid and suggestive, but it’s not proof,” said Brian Balin, Philadelphia College of Osteopathic Medicine. Balin told Alzforum he’d like to see detection of the intact organism, in addition to antigens or DNA, and detection in areas hit early in AD, such as the entorhinal cortex or locus coeruleus.

Another approach would be to identify people with and without the infection, and follow them over time to see who develops AD. Dominy said he’d like to do that, but is focusing on the trial. “We are in the clinic testing a highly specific gingipain inhibitor, and that’s how we want to prove this is causative,” he told Alzforum.

Bacterial Traces: Gingipain in gum tissue from a person with periodontal disease (left) and in hippocampus from a 63-year old with AD (middle), compared with a cognitively normal control. [From Dominy et al., 2019 Science Advances.]

Gingipain not only bestows gum-destroying powers to P. gingivalis, the protease is also neurotoxic, the researchers claim. It killed neurons in culture and upon injection into mouse hippocampus, but its deadly action was blocked by small-molecule inhibitors. These also reversed AD-like changes in a mouse model of periodontal disease.

In that model, the investigators applied P. gingivalis to the mouths of 44-week-old wild-type BALB/c mice every other day for six weeks. After 10 weeks, bacterial DNA was detected in their brains. The infection boosted endogenous mouse Aβ42 levels, and Aβ42 was toxic to P. gingivalis in vitro. The mouth infection led to a reduction in hippocampal neuron number at 10 weeks. Treating mice with gingipain inhibitors starting one week before and continuing for four weeks after the end of bacteria application reduced bacterial DNA and Aβ levels in the brain, and prevented the loss of hippocampal neurons. In the same infection model, COR388 was also reported to reduce brain P. gingivalis DNA and Aβ42, and levels of tumor necrosis factor, a mediator of neuroinflammation.

Cortexyme will begin a Phase 2/3 trial this spring, Lynch told Alzforum. It aims to treat more than 500 people who have mild to moderate AD for one year. The primary endpoint will be cognition measured by the ADAS-Cog. They will also measure P. gingivalis DNA in CSF before and after treatment. The company presented Phase 1 results at the Clinical Trial on Alzheimer’s Disease conference in October 2018. Twenty-four healthy older adults and nine with Alzheimer’s received the drug or placebo for up to 28 days. The treatment appeared tolerable, causing no serious adverse reactions, and no one withdrew.—Pat McCaffrey

References

Therapeutics Citations

News Citations

- Herpes Triggers Amyloid—Could This Virus Fuel Alzheimer’s?

- Aberrant Networks in Alzheimer’s Tied to Herpes Viruses

- Like a Tiny Spider-Man, Aβ May Fight Infection by Cocooning Microbes

Paper Citations

- Leira Y, Domínguez C, Seoane J, Seoane-Romero J, Pías-Peleteiro JM, Takkouche B, Blanco J, Aldrey JM. Is Periodontal Disease Associated with Alzheimer's Disease? A Systematic Review with Meta-Analysis. Neuroepidemiology. 2017;48(1-2):21-31. Epub 2017 Feb 21 PubMed.

- Ilievski V, Zuchowska PK, Green SJ, Toth PT, Ragozzino ME, Le K, Aljewari HW, O'Brien-Simpson NM, Reynolds EC, Watanabe K. Chronic oral application of a periodontal pathogen results in brain inflammation, neurodegeneration and amyloid beta production in wild type mice. PLoS One. 2018;13(10):e0204941. Epub 2018 Oct 3 PubMed.

- Ishida N, Ishihara Y, Ishida K, Tada H, Funaki-Kato Y, Hagiwara M, Ferdous T, Abdullah M, Mitani A, Michikawa M, Matsushita K. Periodontitis induced by bacterial infection exacerbates features of Alzheimer's disease in transgenic mice. NPJ Aging Mech Dis. 2017;3:15. Epub 2017 Nov 6 PubMed.

- Spitzer P, Condic M, Herrmann M, Oberstein TJ, Scharin-Mehlmann M, Gilbert DF, Friedrich O, Grömer T, Kornhuber J, Lang R, Maler JM. Amyloidogenic amyloid-β-peptide variants induce microbial agglutination and exert antimicrobial activity. Sci Rep. 2016 Sep 14;6:32228. PubMed.

External Citations

Further Reading

Papers

- Laugisch O, Johnen A, Maldonado A, Ehmke B, Bürgin W, Olsen I, Potempa J, Sculean A, Duning T, Eick S. Periodontal Pathogens and Associated Intrathecal Antibodies in Early Stages of Alzheimer's Disease. J Alzheimers Dis. 2018;66(1):105-114. PubMed.

Primary Papers

- Dominy SS, Lynch C, Ermini F, Benedyk M, Marczyk A, Konradi A, Nguyen M, Haditsch U, Raha D, Griffin C, Holsinger LJ, Arastu-Kapur S, Kaba S, Lee A, Ryder MI, Potempa B, Mydel P, Hellvard A, Adamowicz K, Hasturk H, Walker GD, Reynolds EC, Faull RL, Curtis MA, Dragunow M, Potempa J. Porphyromonas gingivalis in Alzheimer's disease brains: Evidence for disease causation and treatment with small-molecule inhibitors. Sci Adv. 2019 Jan;5(1):eaau3333. Epub 2019 Jan 23 PubMed.

Annotate

To make an annotation you must Login or Register.

Comments

University of Southampton

University of Southampton

This is a fascinating paper and a breath of fresh air for those of us working in the field. It echoes our own clinical finding in Alzheimer’s disease that periodontitis is associated with cognitive decline and that Porphyromonas gingivalis might be a major mediating factor (Ide et al., 2016). However, the work goes much further than clinical correlation, since it shows for the first time a plausible mechanism for such an effect and may also explain why periodontal treatments (e.g., doxycycline) have not shown any treatment effects. It also nicely reawakens the belief that amyloid is an antimicrobial agent and why removing amyloid or preventing amyloid buildup has not proved to be an effective strategy to date.

Whilst the work does make a compelling case for an important role for P. gingivalis, it is unlikely to be the only bacteria involved in the pathogenesis of the disease, since periodontal infection is associated with a complex, multispecies biofilm and other systemic and central infections have also been implicated. Could blocking the pathogenicity with gingipain inhibitors be therapeutic? Clearly there are other causes for Alzheimer’s disease than periodontitis alone and even here there are likely to be virulence factors other than gingipain (Liu et al., 2017). However, periodontal disease is a major co-morbidity in Alzheimer’s disease and gingipain inhibitors acting to reduce microglial activation and the expression of pro-inflammatory mediators may well have a significant impact on disease progression. This paper makes a compelling argument to find out.

Michael Hurley of the University of Southampton also contributed to this comment.

References:

Ide M, Harris M, Stevens A, Sussams R, Hopkins V, Culliford D, Fuller J, Ibbett P, Raybould R, Thomas R, Puenter U, Teeling J, Perry VH, Holmes C. Periodontitis and Cognitive Decline in Alzheimer's Disease. PLoS One. 2016;11(3):e0151081. Epub 2016 Mar 10 PubMed.

Liu Y, Wu Z, Nakanishi Y, Ni J, Hayashi Y, Takayama F, Zhou Y, Kadowaki T, Nakanishi H. Infection of microglia with Porphyromonas gingivalis promotes cell migration and an inflammatory response through the gingipain-mediated activation of protease-activated receptor-2 in mice. Sci Rep. 2017 Sep 18;7(1):11759. PubMed.

University of Bristol

This paper should be welcomed by those in the Alzheimer’s research community who feel that the antimicrobial protection hypothesis of Alzheimer’s disease should be given more attention.

The case for P. gingivalis as a major player in Alzheimer’s progression is presented well here, in human brain, CSF, and in P. gingivalis-infected mice, and the authors also show that gingipain inhibitors prevent the pathological changes. In particular, the effect of gingipains on tau is an interesting aspect. P. gingivalis is not the only player in Alzheimer’s, however; other researchers have provided good provenance for the presence of other microbes, including various spirochetes, Chlamydia pneumoniae, and viruses such as HSV1.

Knowing at which stage in the disease process that these microbes appear is of importance as the vulnerability of the blood-brain barrier with age may allow many different microbes to pass into the brain; thus, the idea of a spectrum of disease between controls and patients is thought-provoking.

This paper certainly sends a positive message to dentists around the world, that their services are likely to be vital to the well-being of all of us.

University of Central Lancashire

Dominy et al. have provided robust data linking the brain with the main, or keystone, pathogen (Porphyromonas gingivalis) of periodontitis—or gum disease, as it is commonly known. This bacterium appears to migrate from the mouth to the brain of some individuals as they age, and of a significant proportion of subjects who go onto develop Alzheimer’s disease. This further highlights the possibility that Alzheimer’s disease has a microbial infection origin. The article also provides significant advances toward understanding the causal aspects of oral infections, having the potential to cause Alzheimer’s disease and reproduce the hallmark lesions.

This is the first report showing the P. gingivalis genetic footprints (DNA) in the human brains and the associated protease enzymes (x2 gingipains) co-localizing with the essential plaques and neurofibrillary tangles. Dominy et al. also demonstrate that gingipains can break down or fragment the larger biochemical structure of the protein tau. Tau protein is prone to becoming abnormally phosphorylated and if that happens, it has the potential to “collapse” the nerve cell body’s “scaffolding,” called microtubules. This negative event eventually compromises nerve cell function and eventually causes its death. Dominy et al. also show and suggest the appearance of a short tau peptide which they suggest may have relevance to the pathology of this neurodegenerative disease as well as the clinical outcome in the form of poor memory. This again is an original finding.

Dominy et al.’s small-molecule inhibitors reaching clinical trials provides hope of being able to treat/prevent Alzheimer’s disease one day and more importantly, strengthen the direction of the association that oral health is a risk for developing dementia.

Finally, this report is alarming and will hopefully motivate everyone and especially those in their middle ages and those who are entering the “risk age” (65 years+) to maintain adequate oral hygiene. Periodontitis or gum disease can be managed but not cured. A 10-year risk window starts ticking from the time gum disease is diagnosed! This gives an individual time to modify their oral hygiene habits with the help of dental professionals.

Massachusetts General Hospital & Harvard Medical School

Massachusetts General Hospital

Most AD researchers remain to be convinced that microbes are causative in AD. While we agree that the available evidence is not definitive, mounting data suggest microbes are involved in some way with AD etiology. Our own findings show Aβ is an antimicrobial peptide and amyloid is generated to entrap and neutralize microbes; thus, microbes seed amyloid plaques and their presence in brain likely accelerates amyloidosis and the progression of AD pathologies. A link between AD and P. gingivalis in the brain is consistent with this emerging model for microbes in the disease’s etiology.

As with previous studies linking AD to neuroinfection, the key question is which comes first—is it periodontal disease or AD pathology? Understandably, the dental hygiene of people with AD is unlikely to be good and dementia patients are reported to suffer from poor oral health (Syrjälä et al., 2012). The blood-brain barriers of AD sufferers are also weakened and more easily breached. The last several years have seen a number of high-profile studies reporting that AD patients have chronic cerebral fungal, bacterial, or viral infections. This new study fits an emerging pattern of increased susceptibility to chronic neuroinfection among AD sufferers.

Multiple studies have looked for links between oral health and AD. Findings from these studies have been mixed. A recent meta-analysis of previous studies did find a significant association between AD and periodontal disease (Leira et al., 2017). However, for a particular pathogen to be the specific cause of AD, the microbe would need to be present in most, if not all patients. The incidence of P. gingivalis in AD brain reported by Dominy et al is considerably higher than suggested by previous studies. In summary, an increased presence of P. gingivalis in AD brain seems plausible. However, other investigators using larger cohorts need to confirm the Dominy et al. finding of pervasive P. gingivalis neuroinfection among AD patients.

The idea that AD is caused by gingipains directly killing neurons is less convincing and seems inconsistent with overwhelming data linking Ab, tau, and inflammation to neurodegeneration. It is difficult to explain the ubiquitous presence of these key pathologies in AD if neurodegeneration is driven by the direct neurotoxic activity of a microbial toxin. In particular, it’s hard to reconcile the gingipains-mediated neurodegeneration model with AD genetics, e.g., the established finding that mutations in Ab or proteins involved in generating/clearing Ab cause familial AD. Moreover, while previous studies have found poor oral health is linked to dementia, not all AD patients have periodontal disease. Both infected and uninfected patients develop the same hallmark amyloidosis, tauopathy, and neuroinflammation pathologies found in AD brain.

It should be stressed that neuroinfection with P. gingivalis likely remains important for AD even if gingipains prove not to mediate widespread neuronal death. It seems probable that P. gingivalis is a common neurotropic pathogen whose presence in brain has the potential to exacerbate amyloidosis and hasten the onset of dementia.

That said, treatments that target P. gingivalis may prove efficacious for slowing progression in infected patients in the early stages of AD. However, confirming such a benefit in a clinical trial is likely to be challenging. As appears to be the case with Aβ/amyloid, once self-sustaining neuroinflammation takes hold in middle/late AD, there looks to be limited benefit to removing the inflammatory trigger. As is increasingly voiced with regard to therapies that target Aβ, anti-infectives may have to be used before clinical AD symptoms manifest.

References:

Syrjälä AM, Ylöstalo P, Ruoppi P, Komulainen K, Hartikainen S, Sulkava R, Knuuttila M. Dementia and oral health among subjects aged 75 years or older. Gerodontology. 2012 Mar;29(1):36-42. Epub 2010 Jun 30 PubMed.

Leira Y, Domínguez C, Seoane J, Seoane-Romero J, Pías-Peleteiro JM, Takkouche B, Blanco J, Aldrey JM. Is Periodontal Disease Associated with Alzheimer's Disease? A Systematic Review with Meta-Analysis. Neuroepidemiology. 2017;48(1-2):21-31. Epub 2017 Feb 21 PubMed.

The waning presence of mesenchymal stems cells with aging can be linked to a lack of tissue regeneration in periodontal disease. MSCs also play an active role in the innate immune response against organisms such as P. gingivalis. The same low levels of MSCs seen in periodontal disease may be linked to the reduction in hippocampal volume seen in Alzheimer's, as neurons damaged by infection fail to be replaced by MSCs. Note also that MSCs are particularly susceptible to infection by HSV1, such that infected MSCs may fail to differentiate into neural progenitors and mature neurons, also likely connected to reduced hippocampal volume and illustrating a link between active periodontal disease and Alzheimer's, as both conditions involve diminished tissue regeneration capacity due to reduced numbers of viable MSCs.

References:

Misawa MY, Silvério Ruiz KG, Nociti FH Jr, Albiero ML, Saito MT, Nóbrega Stipp R, Condino-Neto A, Holzhausen M, Palombo H, Villar CC. Periodontal ligament-derived mesenchymal stem cells modulate neutrophil responses via paracrine mechanisms. J Periodontol. 2019 Jan 15; PubMed.

Reddi D, Belibasakis GN. Transcriptional profiling of bone marrow stromal cells in response to Porphyromonas gingivalis secreted products. PLoS One. 2012;7(8):e43899. Epub 2012 Aug 24 PubMed.

Chatzivasileiou K, Lux CA, Steinhoff G, Lang H. Dental follicle progenitor cells responses to Porphyromonas gingivalis LPS. J Cell Mol Med. 2013 Jun;17(6):766-73. Epub 2013 Apr 8 PubMed.

Kato H, Taguchi Y, Tominaga K, Umeda M, Tanaka A. Porphyromonas gingivalis LPS inhibits osteoblastic differentiation and promotes pro-inflammatory cytokine production in human periodontal ligament stem cells. Arch Oral Biol. 2014 Feb;59(2):167-75. Epub 2013 Nov 23 PubMed.

Avanzi S, Leoni V, Rotola A, Alviano F, Solimando L, Lanzoni G, Bonsi L, Di Luca D, Marchionni C, Alvisi G, Ripalti A. Susceptibility of human placenta derived mesenchymal stromal/stem cells to human herpesviruses infection. PLoS One. 2013;8(8):e71412. Print 2013 PubMed.

Choudhary S, Marquez M, Alencastro F, Spors F, Zhao Y, Tiwari V. Herpes simplex virus type-1 (HSV-1) entry into human mesenchymal stem cells is heavily dependent on heparan sulfate. J Biomed Biotechnol. 2011;2011:264350. Epub 2011 Jun 21 PubMed.

Sundin M, Orvell C, Rasmusson I, Sundberg B, Ringdén O, Le Blanc K. Mesenchymal stem cells are susceptible to human herpesviruses, but viral DNA cannot be detected in the healthy seropositive individual. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2006 Jun;37(11):1051-9. PubMed.

Make a Comment

To make a comment you must login or register.