Amino Acid Mimicry Leads Researchers to New Resveratrol Target

Quick Links

If some stories are to be believed, the key to a long, healthy life can be found in a bottle of red wine—make that lots of bottles of red wine. Only teeny amounts of resveratrol, a plant compound that increases the longevity of many animals, end up in your favorite vintage. But could that be enough for some health benefits? A new report outlines a role for resveratrol that previously had slipped under the radar. According to a study published December 22 in Nature, the compound binds the enzyme tyrosyl transfer RNA synthetase in the nucleus, triggering activation of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase 1 (PARP1), an enzyme that switches on a slew of genes involved in cellular stress responses, including DNA repair. While the physiological ramifications remain unclear, a smidgen of resveratrol is sufficient to activate PARP1, said study leader Paul Schimmel of The Scripps Research Institute in La Jolla, California.

Resveratrol treatment triggers a response similar to that induced by caloric restriction, which kicks mitochondrial function into high gear and promotes longevity in animals. While new targets for resveratrol continue to pop up, the majority of research focuses on the molecule’s relationship with sirtuin 1 (SIRT1), a deacetylase involved in protective metabolic responses. Resveratrol has been reported to interact with other molecules as well, but whether and how they dovetail with SIRT1 activity is a matter of intense research (see Kulkarni and Canto, 2014).

Schimmel became interested in resveratrol because he studies tRNA synthetases. Unique synthetases anneal each of the 20 amino acids to their respective tRNAs, which then deliver the amino acids to ribosomes for incorporation into growing polypeptide chains. Each tRNA synthetase contains a unique binding pocket that snags its designated amino acid; however, amino acid mimics may also interact with the molecules and facilitate novel functions, Schimmel said. Because resveratrol contains a phenolic ring, as does tyrosine, Schimmel wondered if the plant compound bound tyrosyl transfer RNA synthetase (TyrRS). When cells undergo stress, TyrRS translocates into the nucleus (see Fu et al., 2012), and that is where resveratrol is known to bind its targets.

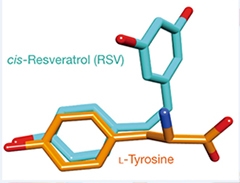

Plant Poseur.

Resveratrol contains a phenol ring, as does tyrosine. The ring allows resveratrol to fit neatly into TyrRS’s binding pocket. [Image courtesy of Sajish and Schimmel, Nature 2014.]

Schimmel and first author Mathew Sajish set out to determine if resveratrol and TyrRS interacted, and if so, to what end? The researchers co-crystalized TyrRS with resveratrol, and found that the two molecules bound tightly. Furthermore, when the researchers treated HeLa cells with low doses of resveratrol, or starved them of serum, TyrRS translocated into the nucleus.

Based on a hunch from a previous study in which the researchers observed that a different tRNA synthetase interacted with PARP1 in the nucleus (see Sajish et al., 2012), the researchers measured the effects of the resveratrol-TyrRS duo on PARP1 activation. PARP1 adds chains of poly ADP-ribose (PAR) to proteins, and it must “PARylate” itself to become fully activated. PARylated PARP1 rose in HeLa cells treated with nanomolar concentrations of resveratrol, and this boost was blocked by Tyr-SA, a tyrosine analogue. The researchers found that at high concentrations, TyrRS could activate PARP1 in extracts or in cells without adding resveratrol. However, resveratrol strengthened TyrRS’s affinity for PARP1.

What might be the consequences of turning on PARP1 in the nucleus? The researchers found that within eight hours of resveratrol treatment or serum starvation, the amount of PARylated proteins in the cells increased, as did the expression of several proteins known to be turned on by PARP1, including Hsp72, acetylated p53, p-AMPK, and sirtuins. Blocking either PARP1 expression or TyrRS expression with short interfering RNAs prevented resveratrol’s activation of the PARP1 pathway. However, knocking down SIRT1 (another known target of resveratrol) did not.

The researchers next looked for evidence of the TyrRS-PARP1 interaction in mice. They injected animals intravenously with 1 micromole, and analyzed proteins in both cardiac and skeletal muscle 30 minutes later. In both, PARylated proteins increased, as did levels of proteins known to be upregulated by the PARylation pathway. When the researchers co-injected a tyrosine analogue along with the resveratrol, these PARP1-dependent effects never occurred.

While the physiological consequences of resveratrol’s activation of PARP1 are unclear, the findings suggest that low levels of the compound may have real effects, Schimmel said. This is important because resveratrol is highly insoluble and has limited bioavailability in the body. In a recent Phase 2 clinical trial for Alzheimer’s disease, patients took a whopping dose (2,000 mg/day), of which only 1 percent reached the cerebrospinal fluid, resulting in nanomolar concentrations there. Despite the exceedingly low amount of resveratrol that found its way into the CSF, patients experienced some improvements in activities of daily living (see Dec 2014 conference story). Scott Turner of Georgetown University in Washington, D.C., who headed the trial, said that the molecular mechanisms underlying these effects were unclear. “Hypotheses will now also include regulation of TyrRS and PARP1 activities,” he commented. He noted that the activation of PARP1 by resveratrol occurred at similar concentrations as those seen in the CSF of patients in the trial.

Jay Chung of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute in Bethesda, Maryland, viewed the results with a healthy dose of skepticism. “While this is an interesting mechanism, it is not clear how relevant it is to the physiological effects of resveratrol because the authors have not addressed that in this paper,” he wrote. Furthermore, he commented that the results do not change the fact that resveratrol has performed poorly in clinical trials so far.—Jessica Shugart

References

News Citations

Paper Citations

- Kulkarni SS, Cantó C. The molecular targets of resveratrol. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2015 Jun;1852(6):1114-1123. Epub 2014 Oct 12 PubMed.

- Fu G, Xu T, Shi Y, Wei N, Yang XL. tRNA-controlled nuclear import of a human tRNA synthetase. J Biol Chem. 2012 Mar 16;287(12):9330-4. Epub 2012 Jan 30 PubMed.

- Sajish M, Zhou Q, Kishi S, Valdez DM Jr, Kapoor M, Guo M, Lee S, Kim S, Yang XL, Schimmel P. Trp-tRNA synthetase bridges DNA-PKcs to PARP-1 to link IFN-γ and p53 signaling. Nat Chem Biol. 2012 Apr 15;8(6):547-54. PubMed.

Further Reading

Primary Papers

- Sajish M, Schimmel P. A human tRNA synthetase is a potent PARP1-activating effector target for resveratrol. Nature. 2014 Dec 22; PubMed.

Annotate

To make an annotation you must Login or Register.

Comments

No Available Comments

Make a Comment

To make a comment you must login or register.