Peter Davies, Beloved Giant of Alzheimer’s Disease Research, Dies at 72

Quick Links

When Peter Davies passed away on August 26, the Alzheimer’s research community lost a brilliant mind, and a truly generous human being. Davies died at age 72, after a long battle with cancer.

His discoveries paved the way for the first Alzheimer’s drugs and uncovered the startling complexity of the tau protein and its role in Alzheimer’s and other tauopathies. In their tributes on Alzforum, fellow scientists particularly recalled Davies’ generous sharing of antibody reagents and spirited conversations with him about the pathophysiology of AD, as much as they saluted his scientific achievements.

Peter Davies

“Peter was clearly one of the greatest investigators in the pantheon of Alzheimer’s researchers. I knew him as a dear friend and valued mentor since the ’80s. I always valued his great balance of scientific objectivity and empathy, especially for young investigators,” Rudy Tanzi of Massachusetts General Hospital wrote to Alzforum.

Davies grew up in Wales, and studied biochemistry at the University of Leeds in northern England. After completing postdoctoral work at the University of Edinburgh, he joined the staff of the Medical Research Council Brain Metabolism Unit there in 1974. It was in Edinburgh that Davies began to explore Alzheimer’s disease.

Published on Christmas Day in 1976, his first AD paper turned out to be a gift to the field. He reported that the cholinergic system took a severe hit in the disease, a discovery that led to the development of acetylcholinesterase inhibitors, the first FDA-approved treatments for the disease (Davies and Maloney, 1976; Alzforum timeline).

His move, in 1977, to Albert Einstein College of Medicine in the Bronx, New York, brought him under the tutelage of the two great (and late) “Bobs” of early Alzheimer’s research in the U.S.—Katzman and Terry. Terry had recruited the young hotshot from England. In 2006, Davies became the scientific director of the Litwin-Zucker Center for Research on Alzheimer’s disease at the Feinstein Institute for Medical Research, North Shore-LIJ Health System, Long Island.

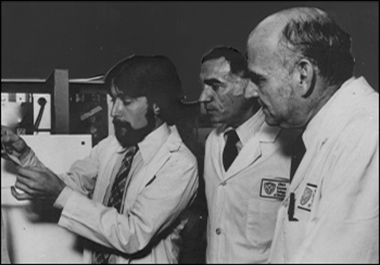

Peter Davies, Robert D. Terry, and Robert Katzman. [Image from Peter Davies.]

Davies is perhaps best known for his work on the myriad forms of tau. He helped lay bare the devilish complexity of this microtubule-binding, tangle-forming protein. Starting with the development of Alz50, the first antibody to latch onto misfolded tau, Davies’ group went on to develop many more such antibodies—including MC-1 and PHF-1—trained against different forms the protein (Wolozin et al., 1986; Greenberg and Davies, 1990; Jicha et al., 1999).

Davies readily shared these reagents with other researchers. “If you ever wanted to obtain and utilize any of the very useful antibodies that his laboratory created and you sent him an email, a few days later the antibody would just appear in your lab,” recalled David Holtzman of Washington University in St. Louis. Throughout the field, Davies’ antibodies proved essential to pivotal discoveries about tau pathobiology (for detail, see Michel Goedert and Maria Grazia Spillantini’s tribute below). “The neuroscience community, and I especially, will be forever grateful for Peter’s generosity in sharing his wonderful library of antibodies and his boundless excitement for scientific discovery,” wrote Ralph Nixon of New York University.

Over more than three decades, Davies published some 250 papers on tau, from its phosphorylation to truncation (Jicha et al., 1999; Weaver et al., 2000; Espinoza et al., 2008; d’Abramo et al., 2013).

He kept an eye toward targeting toxic forms of the protein with therapeutics, and Zagotenemab, a derivative of his MC-1 antibody developed by Lilly, is currently finishing a Phase 2 trial in 285 people with early AD.

Until the End. Peter Davies speaking at the Tau2020 conference held this past February. [Courtesy of Luc Buee.]

Davies also generated mouse models, including the hTau mice expressing all six isoforms of human tau (Duff et al., 2000; Nov 2001 news; May 2011 conference news).

Davies received numerous awards for his scientific achievements, including two MERIT awards from the National Institutes of Health, a Lifetime Achievement Award from the International Congress on Alzheimer’s Disease (ICAD), and the Potamkin Prize for Research in Pick’s, Alzheimer’s, and Related Diseases (Apr 2015 news).

For some years, Davies’ emphasis on the role of tau pathology in AD put him at odds with those who centered their research on amyloid. He was a witty voice for the “tauist” side during the field’s sometimes truculent, and long past, period of division into “baptist-versus-tauist” camps. But for all Davies’ zest for tau, he pursued a broad understanding of the disease.

“Publicly, Peter kept faith as a ‘tauist’ and championed tau’s role in AD and related disorders,” recalled Todd Golde of the University of Florida in Gainesville. “In a more private setting though, Peter always had a quite encompassing view of the complexities of AD.”

“For him, tau was worthy of defense, but it was not a religion,” noted Nixon. “His ecumenicism as a scientist allowed him to embrace varied viewpoints on AD pathogenesis and to convey this broader understanding to junior scientists.”

Davies was a skilled debater. He energetically questioned entrenched assumptions in the field (e.g., Mar 2006 webinar; Jul 2004 conference news). “We had many friendly and interesting discussions about presenilin,” wrote Bart De Strooper of KU Leuven in Belgium. “Despite me being in the amyloid wing of the debates in the field, he liked my work and his comments were, for me—a young scientist at the time—very encouraging and helpful.”

Davies’s deep understanding of the disease made him a sought-after advisor, noted Benjamin Wolozin of Boston University. “Indeed, chatting with Peter into the evening was always an immense pleasure because he always offered a challenging view of the pathophysiology of Alzheimer’s disease.”

Throughout his career, Davies mentored budding researchers, many of whom are still working in the field. “Peter was one of the first people Mike Hutton and I talked to about our JNPL3 tau model, and he did some of the first characterization of the mice,” Jada Lewis of the University of Florida, Gainesville, wrote to Alzforum (Lewis et al. 2000). “Peter believed in our model well before I did. At the time, I was brand-new to the field and had no clue what an honor it was to have Peter involved. I credit this initial collaboration and his subsequent generosity with his resources in helping build my career,” wrote Lewis. “He was a great scientist and mentor, but also a kind and generous human being,” wrote Nikolaos Robakis of Mount Sinai Medical Center in New York.

Perhaps less well known to this audience is that Davies was actively interested in human suffering from schizophrenia. He published around 10 studies on psychosis, in tau transgenic mice, in human cohorts, and at the level of human synaptic neuropathology (Koppel et al,., 2018; Gabriel et al., 1997).

Davies received the inaugural Alzforum Mensch Award in 2002, a more light-hearted time during this website’s early years, when Alzheimerologists used to get together during the Society for Neuroscience meeting for a sometimes raucous hour of comedy, karaoke, and dance shared over beers (Nov 2002 conference news).

More seriously, Davies has been a dear, and always kind, friend of Alzforum from the get-go. Peter was a founding scientific advisor. During the site’s early years, Peter penned conference dispatches for Alzforum (e.g., Sept 2002 conference news). Subsequently, he contributed 25 written commentaries plus countless in-person tips on where the field was headed. He left too soon, and will be missed.

Do you have special memories of Peter? How did he influence your work and career? Found a fun photo? To add to our collective tribute, email gstrobel@alzforum.org or type into the comment field below. —Jessica Shugart and Gabrielle Strobel

References

News Citations

- A Tribute to Robert Katzman

- Robert D. Terry, 93, Co-Founder of U.S. Alzheimer’s Research

- Finally Introducing: A Mouse with Wildtype Human Tau That Makes Tangles

- San Francisco: Tau—Time to Shine as Therapeutic Target?

- Davies, Sperling Share 2015 Potamkin Prize

- Philadelphia: Can a Shrinking Brain Be Good for You?

- Orlando: ARF Awards 2002

- Conference Report "Cell and Molecular Biology of Alzheimer's Disease"

Antibody Citations

Therapeutics Citations

Webinar Citations

Research Models Citations

Image Listing with Navigation Citations

Paper Citations

- Davies P, Maloney AJ. Selective loss of central cholinergic neurons in Alzheimer's disease. Lancet. 1976 Dec 25;2(8000):1403. PubMed.

- Wolozin BL, Pruchnicki A, Dickson DW, Davies P. A neuronal antigen in the brains of Alzheimer patients. Science. 1986 May 2;232(4750):648-50. PubMed.

- Greenberg SG, Davies P. A preparation of Alzheimer paired helical filaments that displays distinct tau proteins by polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1990 Aug;87(15):5827-31. PubMed.

- Jicha GA, Weaver C, Lane E, Vianna C, Kress Y, Rockwood J, Davies P. cAMP-dependent protein kinase phosphorylations on tau in Alzheimer's disease. J Neurosci. 1999 Sep 1;19(17):7486-94. PubMed.

- Jicha GA, O'Donnell A, Weaver C, Angeletti R, Davies P. Hierarchical phosphorylation of recombinant tau by the paired-helical filament-associated protein kinase is dependent on cyclic AMP-dependent protein kinase. J Neurochem. 1999 Jan;72(1):214-24. PubMed.

- Weaver CL, Espinoza M, Kress Y, Davies P. Conformational change as one of the earliest alterations of tau in Alzheimer's disease. Neurobiol Aging. 2000 Sep-Oct;21(5):719-27. PubMed.

- Espinoza M, de Silva R, Dickson DW, Davies P. Differential incorporation of tau isoforms in Alzheimer's disease. J Alzheimers Dis. 2008 May;14(1):1-16. PubMed.

- d'Abramo C, Acker CM, Jimenez HT, Davies P. Tau passive immunotherapy in mutant P301L mice: antibody affinity versus specificity. PLoS One. 2013;8(4):e62402. PubMed.

- Duff K, Knight H, Refolo LM, Sanders S, Yu X, Picciano M, Malester B, Hutton M, Adamson J, Goedert M, Burki K, Davies P. Characterization of pathology in transgenic mice over-expressing human genomic and cDNA tau transgenes. Neurobiol Dis. 2000 Apr;7(2):87-98. PubMed.

- Lewis J, McGowan E, Rockwood J, Melrose H, Nacharaju P, Van Slegtenhorst M, Gwinn-Hardy K, Paul Murphy M, Baker M, Yu X, Duff K, Hardy J, Corral A, Lin WL, Yen SH, Dickson DW, Davies P, Hutton M. Neurofibrillary tangles, amyotrophy and progressive motor disturbance in mice expressing mutant (P301L) tau protein. Nat Genet. 2000 Aug;25(4):402-5. PubMed.

- Koppel J, Sousa A, Gordon ML, Giliberto L, Christen E, Davies P. Association Between Psychosis in Elderly Patients With Alzheimer Disease and Impaired Social Cognition. JAMA Psychiatry. 2018 Jun 1;75(6):652-653. PubMed.

- Gabriel SM, Haroutunian V, Powchik P, Honer WG, Davidson M, Davies P, Davis KL. Increased concentrations of presynaptic proteins in the cingulate cortex of subjects with schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1997 Jun;54(6):559-66. PubMed.

Other Citations

Further Reading

Annotate

To make an annotation you must Login or Register.

Comments

MRC Laboratory of Molecular Biology

University of Cambridge

Peter Davies, who was only 72 years old when he died on August 26, made important contributions to two different areas of research into Alzheimer’s disease. In the 1970s, he was a major proponent of the cholinergic hypothesis of Alzheimer’s disease (Davies and Maloney, 1976). A deficit in neocortical choline acetyltransferase activity, the rate-limiting enzyme of acetylcholine biosynthesis, together with reduced choline uptake and acetylcholine release, as well as loss of cholinergic nerve cells in the nucleus basalis of Meynert, provided evidence for a presynaptic cholinergic deficit in Alzheimer’s disease. This work led to the introduction of cholinesterase inhibitors, which still form a mainstay of Alzheimer’s disease therapy.

The 1980s saw the identification of the major components of plaques and tangles, β-amyloid and tau, and the realization that there is more to Alzheimer’s disease than a cholinergic deficit. In 1985, tau immunoreactivity was identified in the neurofibrillary lesions of Alzheimer’s disease (Brion et al., 1985).

One year later, with Ben Wolozin, Peter described monoclonal antibody Alz-50, which was raised against brain homogenates from patients with Alzheimer’s disease, and distinguished between Alzheimer and control brain homogenates (Wolozin et al., 1986). Alz-50 recognized an antigen named A68 that was present in larger amounts in Alzheimer’s disease than in control brains (Wolozin and Davies, 1987).

At the same time, immunological studies showed that tau is hyperphosphorylated in the neurofibrillary lesions of Alzheimer’s disease (Grundke-Iqbal et al., 1986). In 1988, we identified tau as an integral component of the paired helical filaments (PHFs) of Alzheimer’s disease (Goedert et al., 1988; Wischik et al., 1988a, 1988b). Insolubility of the bulk of PHFs rendered their full molecular characterization difficult. When fiddling with a method for extracting PHFs using sarkosyl (Rubenstein et al., 1986), Sharon Greenberg and Peter obtained a fraction of dispersed filaments (Greenberg and Davies, 1990). By immunoblotting, three major tau bands of 60, 64, and 68 kDa were present. It became apparent that they were the same as A68 (Wolozin et al., 1986) and the previously reported abnormal tau bands in the brains of patients with Alzheimer’s disease (Flament and Delacourte, 1989). In 1991, Virginia Lee and colleagues purified dispersed PHFs to homogeneity and showed that they consist of tau (Lee et al., 1991).

Taken together, these findings established that PHFs are made of tau protein. The ability to extract dispersed PHFs from the brains of patients with Alzheimer’s disease changed much of our work. We vividly remember the excitement we felt when we first saw dispersed PHFs under the electron microscope. We have used sarkosyl ever since, not only to extract tau, but also α-synuclein, filaments (Spillantini et al., 1998). In 1992, we showed that dispersed PHFs are made of all six brain tau isoforms, each full-length and hyperphosphorylated (Goedert et al., 1992). The relative amounts of tau isoforms in PHFs were like those in normal brain. Two years later, it was shown conclusively which isoforms are present in the 60, 64, 68 (and minor 72) kDa tau bands (Mulot et al., 1994).

Peter was co-organizer, with Caleb (Tuck) Finch, of our first meeting (memorable for several reasons) on Alzheimer’s disease, which took place at the Banbury Center in April 1988. We last spoke with Peter at the Tau2020 Global Conference in Washington, D.C., in February of this year. Peter was a good friend, who will be sorely missed. He was fun to be with and liked nothing better than vigorous scientific debate.

Peter is perhaps best known for the production and generous supply of anti-tau antibodies, including Alz-50, MC-1, PHF-1, CP-13 and PG-5. Some of these antibodies are in development for immunotherapy (d’Abramo et al., 2013). Unlike many anti-tau antibodies that are phosphorylation-dependent, Alz-50 and MC-1 recognize an abnormal conformation of tau. They provided important insights into the molecular organization of PHFs and, possibly, their mode of formation (Weaver et al., 2000). The epitopes of Alz-50 and MC-1 are discontinuous and require that the amino-terminus interacts with part of the third microtubule-binding repeat of tau (Jicha et al., 1997).

MC-1 also made it possible to extract tau filaments from Alzheimer’s disease brain using affinity chromatography (Jicha et al., 1999). Like PHFs extracted using sarkosyl (Berriman et al., 2003), these filaments exhibit fiber diffraction patterns characteristic of amyloid (Barghorn et al., 2004). It remains to be determined if the structures and modifications of sarkosyl-extracted and affinity-purified tau filaments are the same.

Most recently, in the electron cryo-microscopy structure of sarkosyl-extracted PHFs, a density that may correspond to residues 7EFE9 from the amino-terminus of tau was found close to K317 and K321 from the third microtubule-binding repeat (Fitzpatrick et al., 2017), providing a structural underpinning for the discontinuous epitopes of Alz-50 and MC-1.

References:

Barghorn S, Davies P, Mandelkow E. Tau paired helical filaments from Alzheimer's disease brain and assembled in vitro are based on beta-structure in the core domain. Biochemistry. 2004 Feb 17;43(6):1694-703. PubMed.

Berriman J, Serpell LC, Oberg KA, Fink AL, Goedert M, Crowther RA. Tau filaments from human brain and from in vitro assembly of recombinant protein show cross-beta structure. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003 Jul 22;100(15):9034-8. PubMed.

Brion JP, Passareiro H, Nunez J, Flament-Durand J. Mise en évidence immunologique de la protéine tau au niveau des lésions de dégénérescence neurofibrillaire de la maladie d'Alzheimer. Arch Biol (Bruxelles). 1985;95:229-35.

d'Abramo C, Acker CM, Jimenez HT, Davies P. Tau passive immunotherapy in mutant P301L mice: antibody affinity versus specificity. PLoS One. 2013;8(4):e62402. PubMed.

Davies P, Maloney AJ. Selective loss of central cholinergic neurons in Alzheimer's disease. Lancet. 1976 Dec 25;2(8000):1403. PubMed.

Fitzpatrick AW, Falcon B, He S, Murzin AG, Murshudov G, Garringer HJ, Crowther RA, Ghetti B, Goedert M, Scheres SH. Cryo-EM structures of tau filaments from Alzheimer's disease. Nature. 2017 Jul 13;547(7662):185-190. Epub 2017 Jul 5 PubMed.

Flament S, Delacourte A. Abnormal tau species are produced during Alzheimer's disease neurodegenerating process. FEBS Lett. 1989 Apr 24;247(2):213-6. PubMed.

Goedert M, Wischik CM, Crowther RA, Walker JE, Klug A. Cloning and sequencing of the cDNA encoding a core protein of the paired helical filament of Alzheimer disease: identification as the microtubule-associated protein tau. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1988 Jun;85(11):4051-5. PubMed.

Goedert M, Spillantini MG, Cairns NJ, Crowther RA. Tau proteins of Alzheimer paired helical filaments: abnormal phosphorylation of all six brain isoforms. Neuron. 1992 Jan;8(1):159-68. PubMed.

Greenberg SG, Davies P. A preparation of Alzheimer paired helical filaments that displays distinct tau proteins by polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1990 Aug;87(15):5827-31. PubMed.

Grundke-Iqbal I, Iqbal K, Tung YC, Quinlan M, Wisniewski HM, Binder LI. Abnormal phosphorylation of the microtubule-associated protein tau (tau) in Alzheimer cytoskeletal pathology. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1986 Jul;83(13):4913-7. PubMed.

Jicha GA, Bowser R, Kazam IG, Davies P. Alz-50 and MC-1, a new monoclonal antibody raised to paired helical filaments, recognize conformational epitopes on recombinant tau. J Neurosci Res. 1997 Apr 15;48(2):128-32. PubMed.

Jicha GA, O'Donnell A, Weaver C, Angeletti R, Davies P. Hierarchical phosphorylation of recombinant tau by the paired-helical filament-associated protein kinase is dependent on cyclic AMP-dependent protein kinase. J Neurochem. 1999 Jan;72(1):214-24. PubMed.

Lee VM, Balin BJ, Otvos L, Trojanowski JQ. A68: a major subunit of paired helical filaments and derivatized forms of normal Tau. Science. 1991 Feb 8;251(4994):675-8. PubMed.

Mulot SF, Hughes K, Woodgett JR, Anderton BH, Hanger DP. PHF-tau from Alzheimer's brain comprises four species on SDS-PAGE which can be mimicked by in vitro phosphorylation of human brain tau by glycogen synthase kinase-3 beta. FEBS Lett. 1994 Aug 8;349(3):359-64. PubMed.

Rubenstein R, Kascsak RJ, Merz PA, Wisniewski HM, Carp RI, Iqbal K. Paired helical filaments associated with Alzheimer disease are readily soluble structures. Brain Res. 1986 Apr 30;372(1):80-8. PubMed.

Spillantini MG, Crowther RA, Jakes R, Hasegawa M, Goedert M. alpha-Synuclein in filamentous inclusions of Lewy bodies from Parkinson's disease and dementia with lewy bodies. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998 May 26;95(11):6469-73. PubMed.

Weaver CL, Espinoza M, Kress Y, Davies P. Conformational change as one of the earliest alterations of tau in Alzheimer's disease. Neurobiol Aging. 2000 Sep-Oct;21(5):719-27. PubMed.

Wischik CM, Novak M, Thøgersen HC, Edwards PC, Runswick MJ, Jakes R, Walker JE, Milstein C, Roth M, Klug A. Isolation of a fragment of tau derived from the core of the paired helical filament of Alzheimer disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1988 Jun;85(12):4506-10. PubMed.

Wischik CM, Novak M, Edwards PC, Klug A, Tichelaar W, Crowther RA. Structural characterization of the core of the paired helical filament of Alzheimer disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1988 Jul;85(13):4884-8. PubMed.

Wolozin BL, Pruchnicki A, Dickson DW, Davies P. A neuronal antigen in the brains of Alzheimer patients. Science. 1986 May 2;232(4750):648-50. PubMed.

Wolozin B, Davies P. Alzheimer-related neuronal protein A68: specificity and distribution. Ann Neurol. 1987 Oct;22(4):521-6. PubMed.

Goizueta Institute @ Emory Brain Health

I was deeply saddened to hear that Peter had passed recently. I had deep respect for Peter as a scientist and a colleague.

Publically, Peter kept faith as a “tauist” and championed its role in AD and related disorders. Especially in the early 1990s, this was extremely important, as the field—led by genetics—largely got into the amyloid camp. Of course, in the long run Peter was more right than wrong, as tau does play an incredibly important role in AD.

In a more private setting, though, Peter always had a quite encompassing view of the complexities of AD. He was not myopic, and also knew how hard it was to figure out the roles of various pathologies—he had been at it a long time.

Sometime in the mid-2000s, I recall reviewing Peter’s NIH R01 grant, and to this day, that grant still stands out as one of the best I have ever read. Not necessarily for the science proposed. Though the science proposed was good stuff, what made the grant exceptional was the deft way in which he acknowledged various aspects and controversies within the field, and then clearly laid out a compelling rationale for what he proposed. It was truly masterful. Someone should try to find that proposal so that others can learn from it.

I also remember debating Peter at an SFN meeting. Peter assumed the “tauist” position and I assumed the “baptist.” This debate was good fun. Lots of posturing but rooted in data and facts. But afterwards at dinner, we had more fun and acknowledged to each other that it was not an either-or proposition.

It is ironic that, even as I write this, I am co-author with Peter on a manuscript from my group relating to recombinant antibodies for tau immunotherapy that I hope will be published soon following some revisions.

Irrespective of science, Peter was a good soul. He had a warm heart and a brilliant, sometimes biting, wit. I, like many, will miss him.

Boston University School of Medicine

I met Peter at the beginning of my career, when I was first starting the Ph.D. portion of my M.D., Ph.D. program. Peter was such an exciting person to work with. He was passionate about research and discovery.

He came into the field with major impact by discovering the cholinergic deficit in Alzheimer’s disease. This discovery led to anti-cholinesterase therapy, which remains a mainstay of treatment for the disease.

The spirit of discovery pervaded my graduate years with Peter. We would sit and talk about the big questions in the field. The environment was incredibly stimulating, with Dennis Dickson, Robert Terry, and Leon Thal all in the mix. Stan Prusiner and others would come by and we would have thoughtful conversations speculating about mechanisms of degeneration.

New York University School of Medicine/Nathan Kline Institute

“I’m not a tauist, I’m a Roman Catholic.” This quote by Peter encapsulates some of the endearing qualities I have appreciated from knowing him over four decades. His quiet sense of humor, his gentle statesmanship, his ability to defend eloquently (and in earlier years, courageously) the importance of tau yet stay above the scientific fray that could turn debate into crusade.

For Peter, tau was worthy of defense but it was not a religion. His ecumenicism as a scientist allowed him to embrace varied viewpoints on AD pathogenesis and to convey this broader understanding to junior scientists. This he did annually at the Charleston Conference on AD that brings promising young AD researchers together for three days of career mentoring by a small senior group. This was a special quality time I was lucky enough to share with Peter.

Being a cytoskeleton biologist, I was even more fortunate to have a continuous relationship over these many years, from sending him my best undergraduate for Ph.D. training in 1980 to sharing a program project on tau, many, many site visits/NIH panels, and some memorable road trips back to New York from D.C.

The neuroscience community, and I especially, will be forever grateful for Peter’s generosity in sharing his wonderful library of antibodies and his boundless excitement for scientific discovery.

Massachusetts General Hospital

Peter was clearly one of the greatest investigators in the pantheon of Alzheimer’s researchers. I knew him as a dear friend and valued mentor since the '80s. I always valued his great balance of scientific objectivity and empathy, especially for young investigators.

Maya Angelou told us that we don’t remember what people said or did in their lives, but how they made us feel. From my earliest days as an Alzheimer’s researcher, in every interaction, Peter always made you feel like your scientific ideas and views mattered.

And, in his own science, he was dogged. I believe Peter was the first to discover that tangles were made of tau, even though, early on, he stubbornly insisted on calling it a novel protein, called A68. Since that time, he was arguably the staunchest supporter of the importance of tauopathy in the field, and his input along those lines is now invaluable.

But, importantly, Peter was always willing to keep his mind open about the role of Aβ.

As a friend and colleague, I remember so many times when Peter would hear me say something in a talk or in a public comment that he found questionable, he would immediately reach out to me and challenge me on it, not only to learn more, but just as much out of a desire to help me out.

Peter was one in a million. When I think about him now, I not only remember his brilliant science and engaging talks, but I mostly recall his friendship, infectious enthusiasm for science, and, especially, his enduring kindness as a human being. He will be dearly missed.

UK Dementia Research Institute@UCL and VIB@KuLeuven

With Peter, the field loses a pioneer and a charismatic and inspiring leader. Personally, it feels like losing a friend. His work was fundamental to the acetylcholine hypothesis and the first drugs for Alzheimer’s disease. In later years, he focused on tau pathology in Alzheimer’s disease, his monoclonal antibodies being the gold standard to detect abnormal conformations of tau.

We had many friendly and interesting discussions about presenilin. Despite me being in the amyloid wing of the debates in the field, he liked my work and his comments were, for me—a young scientist at the time—very encouraging and helpful.

Peter was a great scientist, a wise man, and a good friend. We will miss him dearly.

Global Alzheimer's Platform Foundation

The publication by Peter Davies and A.J. Maloney in The Lancet (1976) describing the selective loss of central cholinergic neurons in autopsy-verified cases of Alzheimer’s disease provided much of the scientific motivation to test the effects of cholinesterase inhibitors in patients with AD.

The paper greatly impressed me and Kenneth Davis, both junior researchers on the staff of the Psychiatric Clinical Research Center at Stanford University in 1976. We quickly began testing the effects on physostigmine as well as other cholinergic drugs on patients with AD, first at Stanford and later at Mount Sinai School of Medicine in New York. Peter’s work was confirmed and extended by Elaine and Robert Perry, David Bowen, and others and remains a key part of our scientific understanding of this disease.

Along with several colleagues at Mount Sinai I had the good fortune to collaborate with Peter on several projects after he moved to the Albert Einstein College of Medicine in New York. Peter was always curious, innovative, scientifically rigorous, and a generous scientific colleague.

After moving to work for Eli Lilly and Company in Indiana, I continued to see Peter at scientific meetings and to follow his work. With others on the board of directors of the Indiana chapter of the Alzheimer’s Association, we invited Peter to give the keynote presentation at the chapter’s Annual Meeting in 2012. He not only gave a wonderful talk that was well received by a large lay audience, he insisted on paying his own expenses and refused the honorarium. As always, devoted to science and seeking to improve human welfare.

RIKEN Center for Brain Science

My colleagues and I express sincere condolences to the family of the late Peter Davies. His passing is such a big loss to the research community.

I have had several opportunities to communicate with Peter via telephone and email, although I did not have a chance to meet him in person because of the distance between New York and Tokyo. Peter was so generous to provide us with antibodies raised to various forms of tau protein, i.e. CP13, MC1, PHF-1, and RZ3. The antibodies have helped us with our published studies (Hashimoto et al., 2019; Saito et al., 2019) and will do so from now on, too. I believe that all the AD researchers who study the biology and pathology of tau protein benefit from Peter’s achievement.

There is one thing that I have always wondered. Why did he not commercialize these antibodies? He would have profited, and he would have saved time and energy for shipment of the antibodies. I can only speculate that it was his philosophy to support the research community by providing the resources free of charge.

Less known is Peter’s discovery about reduced levels of somatostatin in AD brain, published in Nature in 1980 (Davies et al., 1980). This paper inspired us to identify somatostatin as an activator of Aβ-degrading enzyme neprilysin (Iwata et al., 2001; Saito et al., 2005). Reduction of somatostatin may account for the aging-associated Aβ accumulation in brain. The series of work, the tradition of which had been initiated by Peter, may lead to generation of new medication candidates because the responsible somatostatin receptor subtypes among five have been identified (Nilsson, 2020).

References:

Hashimoto S, Matsuba Y, Kamano N, Mihira N, Sahara N, Takano J, Muramatsu SI, Saido TC, Saito T. Tau binding protein CAPON induces tau aggregation and neurodegeneration. Nat Commun. 2019 Jun 3;10(1):2394. PubMed.

Saito T, Mihira N, Matsuba Y, Sasaguri H, Hashimoto S, Narasimhan S, Zhang B, Murayama S, Higuchi M, Lee VM, Trojanowski JQ, Saido TC. Humanization of the entire murine Mapt gene provides a murine model of pathological human tau propagation. J Biol Chem. 2019 Aug 23;294(34):12754-12765. Epub 2019 Jul 4 PubMed.

Davies P, Katzman R, Terry RD. Reduced somatostatin-like immunoreactivity in cerebral cortex from cases of Alzheimer disease and Alzheimer senile dementa. Nature. 1980 Nov 20;288(5788):279-80. PubMed.

Iwata N, Tsubuki S, Takaki Y, Shirotani K, Lu B, Gerard NP, Gerard C, Hama E, Lee HJ, Saido TC. Metabolic regulation of brain Abeta by neprilysin. Science. 2001 May 25;292(5521):1550-2. PubMed.

Saito T, Iwata N, Tsubuki S, Takaki Y, Takano J, Huang SM, Suemoto T, Higuchi M, Saido TC. Somatostatin regulates brain amyloid beta peptide Abeta42 through modulation of proteolytic degradation. Nat Med. 2005 Apr;11(4):434-9. Epub 2005 Mar 20 PubMed.

University of Texas, Southwestern Medical Center

Peter was an enormously kind man, generous with his time and resources. He influenced our work by creating terrific monoclonal antibodies against tau, which he shared willingly and repeatedly. These reagents were essential to a number of our published studies.

When challenged on his ideas, he was always entirely gracious. I was very, very fond of him, and will miss him.

University of Nevada Las Vegas

I was saddened to hear that the world of AD, and all of us who knew Peter, had lost him. His early discoveries regarding the cholinergic system were highly influential in leading to the development of cholinergic therapies. His work and these drugs comprise a key milestone in the history of AD.

His bright smile, quick intellect, and good nature embraced all who knew him. We will miss him and his guiding light.

Mount Sinai School of Medicine, NYU

I have known Dr. Peter Davies for more than 30 years. I first met him in 1986 at a Bunbury Symposium on the Molecular Neuropathology of Aging that he organized at Cold Spring Harbor Laboratories. Peter made significant and lasting contributions to the neuropathology of AD and specifically to tau-related neuropathology.

In addition, he helped many AD researchers, especially young ones, by providing them with anti-tau antibodies, which he had a special ability to make and characterize.

His contributions to the AD field included the successful mentoring of a large number of researchers, many of them still working in the AD field. He was a great scientist and mentor, but also a kind and generous human being. He will be sorely missed by the AD community.

retired from IIBR

I was extremely saddened to read that Peter Davies died recently. His pivotal and pioneering study published in Lancet with A.J. Maloney indicated the importance of cholinergic hypofunction in Alzheimer’s disease and provided the rationale for the development of cholinergic therapies (Davies and Maloney,1976). It was my honor to invite Peter as a plenary speaker to the International Conference on Alzheimer’s and Parkinson's Diseases in 1989 in Kyoto (Japan), and also as an invited speaker to ADPD 1997 in Eilat (Israel). We all enjoyed his excellent and didactic lectures. The world of AD researchers lost one of his most prominent scientists.

References:

Davies P, Maloney AJ. Selective loss of central cholinergic neurons in Alzheimer's disease. Lancet. 1976 Dec 25;2(8000):1403. PubMed.

Co-Director, Brigham and Women's Hospital's Ann Romney Center for Neurologic Diseases

Like many others in our field, I was greatly saddened by the news that Peter Davies had died. I came to know Peter in the mid-1970s, when he led one of three research teams in the United Kingdom that first defined the cholinergic deficit which occurs so prominently in Alzheimer’s disease. Peter’s seminal work on what was initially referred to as the “cholinergic hypothesis” of Alzheimer’s underpinned the development of the first symptomatic treatment for the disease, acetylcholinesterase inhibitors, which remain a mainstay of therapy that I prescribe routinely to my patients. Very few of us can claim we helped precipitate a successful treatment paradigm for a human disease; Peter rightly could.

As an intensely curious, sometimes iconoclastic thinker about pathobiology, and as a disciple of his good friend Robert Terry, Peter soon turned his attention to neurofibrillary degeneration in AD and the key role of the tau protein. Among his many contributions in this area, I found his development of the renowned Alz-50 monoclonal antibody and its characterization particularly compelling. I recall that Peter first felt the A68 antigen which Alz50 recognized in brain tissue might be a very special molecule, even as some of us thought it might be a form of tau. Peter and his colleagues, including his talented student Ben Wolozin, brought clarity when they showed Alz50 recognized a specific phosphorylated species of tau that accumulates in virtually all AD brains. With Alz50 and other unique antibodies that his lab created, Peter was highly generous, shipping his reagents to myriad investigators around the world.

Peter and I shared the first Metropolitan Life Award for Alzheimer’s Disease in 1986, and I recall vividly the formal award ceremony at the Pierre Hotel in Manhattan and then my family and his bumping into each other afterwards at the Hard Rock Café on 57th Street. There, and everywhere our paths crossed, I found Peter to be a warm and wonderfully humorous fellow, and his English baritone accent and lilting delivery always held his listeners’ attention.

In the strange period when Alzheimer research seemed to be split into competing paths of “Tauists” and “Baptists,” Peter successfully defended the central importance of tau dyshomeostasis, and he was right. It took a while for all of us to realize that both camps were scientifically correct—it was just a matter of coming to understand the sequence and impact of these complex contributions to the development of the disease, and the fact that they were certainly not the only key events.

I find it especially sad that Peter will not be with us to witness the almost certain success of anti-tau therapeutics, something he worked on so creatively, and to see them joined with the anti-Aβ treatments that are also emerging. Peter so loved—and lived—the chase for clearer knowledge; we will remember him as the progress to which he contributed so effectively comes to bear fruit in the real world.

University of California, Irvine

I was greatly saddened to hear of Peter’s passing. He was a Goliath in the Alzheimer’s field, and he leaves an enduring legacy. I deeply admired and respected his science and personality. Although he might be considered dogmatic, I always found him to be quite open and willing to discuss different points of view. In addition to his vast contributions to the field, Peter was just a fun person to be around, whether it be at a meeting, restaurant or a bar. Like so many of my colleagues, I will miss this kind, witty, and fun-loving gentleman. His is a profound loss for the field.

DZNE, German Center for Neurodegenerative Diseases

DZNE (German Center for Neurodegenerative Diseases)

We were shocked by the news of the untimely death of Peter Davies, and we second all the thoughtful and warm remarks made by colleagues about the remarkable person he was.

We met Peter on numerous occasions at SfN or Alzheimer meetings. In the late 1980s our research was drifting from an earlier focus on microtubules to a focus on tau, in a lab located in the middle of a synchrotron radiation facility, far away from a clinical environment. Peter's continuous advice was an important source of inspiration. It also helped us survive amidst the intricacies of a medical controversy pitting baptists against tauists, where even some granting agencies considered tau research as peripheral to the Alzheimer problem.

Like others, we benefited from Peter's generosity with reagents like antibodies and preparations of AD tissue samples. This resulted in three co-authored papers dealing with structural aspects of PHFs, but his spirit was present in many other publications.

Peter's enormous impact on AD research has already been acknowledged by the previous comments; here we would like to add one particular paper that helped spawn a new direction, tau phosphorylation, the relationship with cell-cycle events (e.g., kinases in mitosis) and the fate of neurons (Vincent et al., 1996).

At the time we were working on a similar theme (Preuss et al., 1995), which later led to the "jaws" model of tau-microtubule interactions (Preuss et al., 1997). Needless to say, Peter's antibodies were essential tools in these studies. His insights led to the wide recognition of aberrant cell cycle re-entry in neurons, recently merging with the field of senescence and leading to novel approaches to treatment.

We will miss Peter's friendly style of discussions, mixed with British humor, and farsighted guidance.

References:

Vincent I, Rosado M, Davies P. Mitotic mechanisms in Alzheimer's disease?. J Cell Biol. 1996 Feb;132(3):413-25. PubMed.

Preuss U, Döring F, Illenberger S, Mandelkow EM. Cell cycle-dependent phosphorylation and microtubule binding of tau protein stably transfected into Chinese hamster ovary cells. Mol Biol Cell. 1995 Oct;6(10):1397-410. PubMed.

Preuss U, Biernat J, Mandelkow EM, Mandelkow E. The 'jaws' model of tau-microtubule interaction examined in CHO cells. J Cell Sci. 1997 Mar;110 ( Pt 6):789-800. PubMed.

retired from NIH/NIA

I am also very saddened to learn of Peter Davies' passing. I first met him in the middle 1980s, when I invited him to chair Alzheimer's disease grant application review panels for the NIA/NIH. His sense of humor and good spirits always made the review meetings more fun. I then became his NIA Program Officer on a series of grants, including his Leadership and Excellence in Alzheimer's Disease (LEAD) award, given only to the top scientists in the field. He continued to contribute important research findings throughout the remainder of his career.

We last spoke at the Tau Consortium meeting last February where, despite his health problems, he opened the meeting. His wit and warmth will be missed by all who knew him.

Johns Hopkins University

I’m deeply saddened to hear about Peter Davies’ demise. He had a profound influence on my early career. He was one of three speakers at a satellite preconference meeting at the first SFN I attended, in Dallas. I believe that was 1985—my initial entrée into the field when I was beginning to search for some meaningful AD-related science. Dennis Selkoe, Cliff Saper, and Marcus Raichle were the others.

Peter also put together a study section comprising young and upcoming investigators who were “unknown” at the time. It was during that study section, at some time in the late 1980s, that I found myself sitting around a table reviewing grants with Rudy Tanzi, Sam Sisodia, and others.

But rather than go into his impactful science and generosity as have others, I’ll share a few amusing vignettes.

Peter became a friend. I had him as a visiting speaker in my early days at Upjohn. The no-smoking rule there was a challenge. He and I took frequent breaks outside so that he could grab a dose of nicotine.

We spent numerous hours together at pubs. At an SFN in New Orleans, he and I were having one of our classic laughter-filled scientific discussions at a bar on the Riverwalk, on the opposite side of the convention center. Peter was the Grass Lecture speaker that evening which was scheduled for 6 p.m. We lost track of time. He looked at his watch, I believe it was 6:05. He looked up and said, “Sh*t! I’m late!” As we were running back I commented to him, “Well, since I’m with you, I guess I’m not.”

At a subsequent SFN in New Orleans, I was out walking on Bourbon Street when I looked down at the sidewalk and found a green card. Picking it up, I saw that it had the name Peter Davies on it. I put it in my pocket, found him the following day in the poster sessions, and walked over to ask him if he’d lost something. He asked what I was talking about. I handed him his green card.

Peter always reminded me a bit of Dudley Moore, who starred in the movie “Arthur.” Taking a lyric from the theme song of that movie sung by Christopher Cross, perhaps it applies to our dear friend Peter and may be part of the reason I thought that he favored Arthur:

"Arthur he does as he pleases

All of his life, he's mastered choice

Deep in his heart, he's just, he's just a boy

Living his life one day at a time

And showing himself a really good time

Laughing about the way they want him to be."

Peter was a lovely man. I’m one of many hundreds of people who owe him more than we could ever repay. But he didn’t seek any sort of repayment. Rather, as he did, we just need to pay it forward to others.

Barrow Neurological Institute

I was deeply saddened upon hearing of the passing of Peter Davies. Peter's pioneering work contributed greatly to our understanding of the roles that the cholinergic system and tau play in the pathogenesis of the Alzheimer's disease (AD). Although I only had the honor of meeting Peter a few times, our conversations were always interesting and covered a broad band of topics.

He was extremely generous when it came to providing his antibodies to others for their research. I remember the first time I sent him a request for the ALZ50 antibody, I heard nothing for a long time and then one day a package arrived containing what appeared to be a liter of ALZ50, with no note. He never requested authorship in exchange for his antibodies.

Not only was Peter one of the most prominent scientists in the field of AD research, he was a was a true gentlemen and a great colleague. He will be missed!

University of New Mexico

No words can describe how sorry I feel for the loss of Dr. Peter Davies—a true legend and leader in the area of tau biology, in general, and tau pathology relevant to Alzheimer's disease and related tauopathies. His friendly and collaborative nature has immensely supported the research community with the most valuable research resources in tau research (e.g. MC1, Alz50, PHF-1 tau antibodies, and mouse models of tauopathy). He will be dearly missed and our hearts go out to his family and friends.

University of Virginia

Peter was both a great scientist and a consummate gentleman. His generosity sharing reagents is testimony to his selflessness. He will be sorely missed.

CurePSP

There are those who have known Peter since the discovery of Tau and those, like me, who met him only a few years ago. Yet despite the different time frame, we all use similar words to describe him: gentle, kind, encyclopedic, great debater, even-tempered, astute communicator, generous with his knowledge, time, and reagents. A true gentleman! We all agree, there are not too many like Dr. Peter Davies.

I had the honor to have Peter join the scientific advisory board of a program I was running prior to joining CurePSP (I was then at Cohen Veterans Bioscience). Peter helped us find common ground within an alliance of mechanistic modelers, mathematicians, programmers, and Tau neurobiologists. The goal was to create an actionable computer model that represented the state of knowledge (and the gaps) related to Tau biochemistry, molecular, and cell biology.

Peter was the perfect advisor. I visited his office in 2018 and we discussed bioavailability of immunoglobulin as a function of brain vasculature complexity. He loved the idea of bringing quantification to qualitative science. These interactions changed me, and I’m forever grateful. I hope there’ll be a worthy memorial and a place where people can aggregate and share all the content they have accumulated while connecting, working, and learning with Maestro Peter Davies!

Lille Neuroscience & Cognition

It is with profound sadness that I learned of the death of Professor Peter Davies. What terrible news. Peter was a mentor to many of us. A pioneer in the cholinergic hypothesis, he was quickly interested in tau protein. He then became a leader in the tau field and he defended, without being dogmatic, this topic until his last breath.

Peter cannot be summed up with all the awards he has received during his career. Peter deserves the award for humility and kindness. He also reminded us that science, before being competitive, must be collaborative. All the tauists used his CP-13, MC-1, PHF-1 antibodies ... and his experimental models such as htau mice. Peter was an extraordinary scientist and a great man.

On a personal note, I was fortunate to meet Peter very early in my career and he clearly inspired me. I first met him at a conference at Mount Sinai Hospital, New York City, in late 1989 and then at the Second International Conference on Alzheimer's disease and related disorders in Toronto in July 1990. We have been talking to each other ever since. Peter has hosted some of my former thesis students in his laboratory. Finally, the Rainwater Prize selection committee meetings were my last chance to see and talk with him.

We need to pay him the tribute he deserves.

BrightFocus Foundation

BrightFocus is mourning the loss of Dr. Peter Davies. We are especially proud and grateful to have had him serve as a member of our Alzheimer’s Disease Research Scientific Review Committee from 1989 to 2000, and co-chair for six of these years. His leadership and guidance for funding innovative research has made a lasting impact in early career support for many of our grantees, many of whom have gone on to make a significant impact in their respective fields, and helped to catalyze a broad spectrum of Alzheimer’s disease and related dementia research.

I had the distinct pleasure of recently serving with him on a tauopathy advisory group, where I witnessed his passion for mentorship of early career investigators and his desire for the scientific community to work together toward a common goal. All of us at BrightFocus extend our sympathy to Dr. Davies’ family and colleagues around the world. We are honored to have known him and to have benefited from his wisdom and expertise.

Indiana University School of Medicine

I am profoundly saddened to learn that Peter Davies passed away. I've always had tremendous respect for Peter, both as a scientist and a person. He was an extraordinarily gifted researcher, brilliant thinker, and a man of genuine warmth and generosity.

I fondly remember when I met him in New York during my days at Mount Sinai School of Medicine and benefitted from his deep knowledge of Alzheimer's disease, particularly the intricacies of tau epitopes. Later, while working on cholinesterase inhibitors, I was impressed with his discovery of the cholinergic deficit in Alzheimer’s in 1976. Even more impressive is how his discovery evolved as knowledge in the field improved.

Later I sought his wisdom when starting a journal, Current Alzheimer Research (CAR), 17 years ago. A new journal with no indexing and impact factor made me wonder who would spare time. He did! As we all remember the first car we drove in life, so do CAR readers remember his contribution and greatness.

As we mourn the untimely passing of Peter Davies, we will miss his warm heart and dazzling mind. Peter’s passion for research and innovation and human kindness is truly inspiring.

Medical College of Wisconsin

I am saddened to see the loss of another colleague from the early days of Alzheimer's research. His identification of a neurotransmitter change in Alzheimer's disease in 1976 offered the hope we could soon develop a pharmacological strategy for this disease. The enthusiasm generated by Peter Davies' work led to the first AD-dedicated conference at the NIH in 1977 and the following year in Europe at the University of Florence, Italy. Due to Peter's work, many of us young aspiring researchers decided to make Alzheimer disease our life's work. His professional example and kind persona will always be remembered.

UC Irvine

I am very saddened to learn of Peter's passing. I met Peter just last year at the Charleston Conference Alzheimer's Disease in 2019 (newvisionresearch.org). Peter was so generous to a newcomer in the field, even suggesting potential collaborators he knew. During dinner, his "you won't believe it but it's true" story was that he was a very active rugby player. All of us, encouraged by Peter in our ideas for new projects during the conference, will miss him.

Casma Therapeutics

I was very sad about Peter's passing. Peter was a beloved researcher indeed! It is a big personal loss and for the AD field.

I learned so much from Peter. He was a great mentor and such a good human being. It was so fun to work side-by-side with Peter in the tissue culture hood. He was excited to find out I was a lefty, so that we could work in the hood at the same time and get more done!

He was such a generous scientist who always shared everything he could, from information to reagents. I believe without Peter, the AD field wouldn't have advanced at the same pace. He touched many lives, and he probably provided antibodies to every researcher in the world working on AD and Tau.

I applied to Einstein because of Peter and moved to the U.S. to study with him. He changed my career in a profound way and taught me much about the human brain.

He will be missed, but his work and antibodies will continue to impact the field for a long time.

Medical University of South Carolina

With Peter's death, we have all lost a major leader in the AD field. It is really very sad.

Fes Cuautitlan. UNAM

I am so sorry for this news. Peter Davies always had his selfless support. I always support my work with the antibodies that he developed against the tau protein. He was an extraordinary scientist and a great person.

Scripps Research Inst.

In this pandemic year, there have been no hallways at conferences where I can connect with old friends and colleagues. I am belatedly sad to hear about Peter's passing. I admired Peter greatly. He was a dedicated scientist and the field is diminished by his loss.

Make a Comment

To make a comment you must login or register.