As RNA Therapies Come of Age, Efficacy Remains Weak

Quick Links

Recent approvals of antisense therapies for spinal muscular atrophy and Duchenne muscular dystrophy have bolstered hopes for targeting RNA to treat a plethora of neurodegenerative brain disorders. At the 70th annual meeting of the American Academy of Neurology, April 21 to 27 in Los Angeles, scientists heard the latest results about nusinersen, an FDA-approved antisense oligonucleotide (ASO) for the treatment of childhood spinal muscular atrophy, and about inotersen and patisiran, antisense- and siRNA-based drugs, respectively, for the treatment of transthyretin amyloidosis.

- RNA-targeting therapies for spinal muscular atrophy and transthyretin amyloidosis show benefits years out.

- Patients treated earlier fare better.

- Treatments are pricey and fall well short of being a cure.

The data suggest patients can continue to improve years after starting treatment, and that the earlier they start, the better. Still, the treatments fall far short of cures and costs are staggering. Antisense treatments for Huntington’s, ALS, and tauopathies are in early stage trials and seem safe (see Part 2 of this story).

Steady but Small Improvement from Nusinersen

Diana Castro, UT Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, reviewed new clinical data on nusinersen. Ionis Pharmaceuticals of Carlsbad, California, designed this ASO to compensate for mutations in the gene for survival motor neuron 1 (SMN1). By altering gene splicing, nusinersen bolsters production of the full-length version of the nearly identical SMN2. The ASO made headlines in 2016 when interim analyses of two Phase 3 trials revealed that children taking the drug had improved on tests of motor function and had better odds of surviving (Finkel et al., 2017; Mercuri et al., 2018). The trials were stopped to allow all children to switch to the drug in an open-label extension trial (Nov 2016 news).

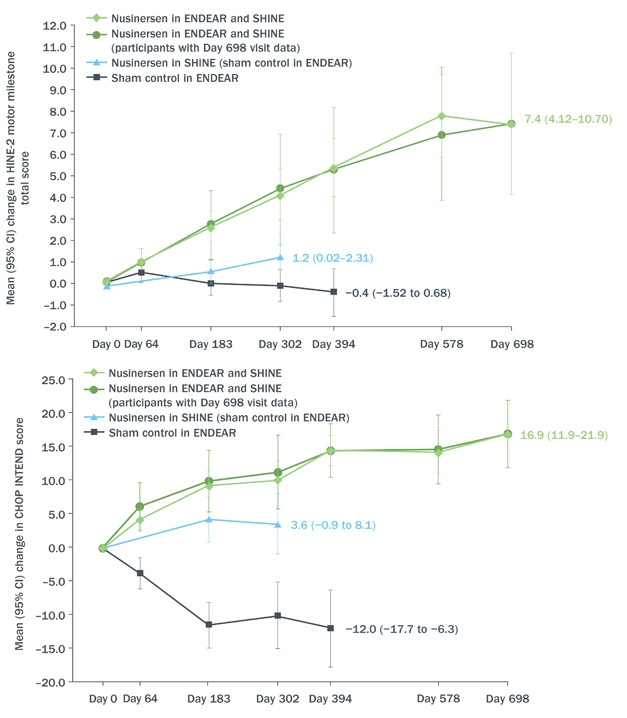

Castro reviewed data from the Phase 3 ENDEAR study combined with interim results as of June 30, 2017, from the open-label extension SHINE (see image below). ENDEAR enrolled 122 babies who had been diagnosed as most likely having SMA type 1, the severest kind. Of the 81 who received nusinersen, 65 transitioned into SHINE, as did 24 of 41 who had been on placebo. All started their intervention when they were seven months old or younger. In both ENDEAR and SHINE, nusinersen was delivered into the cerebrospinal fluid. Four loading injections a few weeks apart were followed by maintenance injections every four months. Each injection delivered 12 mg of nusinersen.

Still Going. From day zero of open-label extension, babies who received nusinersen at seven months or younger (green) continued to benefit according to HINE-2 (top) and CHOP-INTEND (bottom) neurological tests of infant development. Those who switched from placebo to drug around 18 months of age improved, as well (blue), at least compared to their prior deterioration during the placebo-controlled phase of the trial (black). [Courtesy Diana Castro, UT Southwestern Medical Center.]

Of the 81 babies who started treatment in ENDEAR, 12 could sit independently, and 23 were able to control their head movements fully at the time of their last assessment—for some, nearly three years after receiving their first dose. Sitting and head control are developmental milestones that babies with SMA1 are not expected to achieve. Although none could stand or walk independently, mean motor function had continued to improve for the group, changing by 5.8 on Section 2 of the Hammersmith Infant Neurological Examination. This measure of infant motor development assigns scores of zero to four in eight categories, from controlling head movement to sitting, kicking, crawling, and eventually walking. Clinicians deemed 51 of the 81 infants “responders,” based on their scores in individual categories of the HINE-2. Responders were those who improved in more categories than they worsened, or improved by one or more points in six of the eight categories on the scale. The Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia Infant Test of Neuromuscular Disorders (CHOP INTEND), a similar test designed for evaluating very weak kids, indicated improvement in motor function in 55 patients.

The drug extended life. The median time to death or respiratory failure for infants who received nusinersen at seven months or younger was 73 weeks, compared with 23 weeks for those who started in the placebo group.

Moreover, although 12 of the 24 babies who had received placebo in ENDEAR needed permanent respirator assistance by the start of the extension, this group as a whole seemed to stabilize during SHINE, registering a small mean improvement of 1.1 on the HINE-2, and four children qualified as responders. However, of the 12 children who started SHINE free of permanent respirator assistance, five had died or gone on permanent ventilation.

In discussion, John Day, Stanford University, and Richard Finkel, Nemours Children’s Hospital in Orlando, Florida, noted that other studies of nusinersen point to the potential for improvement in older children or even in adults with SMA. “There may be a small pool of more resilient motor neurons that can be rescued,” suggested Finkel.

Consistent with results from previous trials, there were no serious events in SHINE that seemed related to treatment. Fever and upper respiratory tract infections were the most frequent adverse events.

Positive results also emerged from EMBRACE, a two-part, Phase 2 safety study testing nusinersen in 21 children between seven and 49 months old who had SMA. EMBRACE accepted children who were excluded from earlier nusinersen trials for a variety of reasons, including age at symptom onset and how many copies of mutant SMN2 they carried. Because the gene is highly prone to genetic duplication, SMN2 copy number can be as high as four, and, in general, more copies means milder symptoms. Children who completed the 14-month blinded period could go on to the 30-month, open-label part 2 of the study. Primary outcomes were safety and tolerability, with secondary objectives being pharmacokinetics.

Perry Shieh from the University of California, Los Angeles, presented safety data from the first part of EMBRACE. “[Nusinersen] demonstrated a favorable safety profile with no new or unexpected safety signs,” he said. Five children in the treatment arm and three in the placebo had serious adverse events, but none were thought to be related to the treatment. Also, exploratory measures of motor function hinted at improvement. Seven of nine children who had symptoms of SMA before they were seven months old improved in more HINE categories than they worsened in. In contrast, none of the four children with SMA type 1 who were on placebo responded. In eight children with later-onset disease, those taking nusinersen scored better on the HINE, with a mean improvement of approximately five points on day 302, compared with zero for those on placebo. However, two of three children in the placebo group also qualified as responders, suggesting that improvements may be unrelated to drug or the criteria for responder is not stringent enough. Twenty children have now enrolled in EMBRACE part 2.

Results from an even smaller cohort of children with SMA type 2 or 3 who participated in a clinical trial and its open-label extension also hinted at nusinersen benefits. These diseases are milder and start later than type 1 SMA, and patients usually have three or more good copies of SMN2. Children with SMA 3 can stand and walk, although some may require aids, while those with SMA 2 are usually unable to do either independently. Jacqueline Montes, Columbia University, New York, presented data on the 14 children who could walk during the CS2 or CS12 trials and had performed a six-minute walk test. The group included kids aged 2 to 15, 13 of whom had SMA 3 and one who had SMA 2. Except for one child, all were able to walk independently. Montes reported that these children walked a median of 17 additional meters at day 253, and 98 meters farther than a baseline median of 251 meters at day 1,050 of treatment.

Attendees also learned how patients on nusinersen are faring in private practice. Physicians began treating patients with nusinersen even before it was on the market because Biogen’s “expanded access program” allowed them to request the drug for patients not eligible or able to participate in trials. “We’re starting to get real-world data, including some from older patients with a variety of symptoms,” said Finkel. He and Day presented case studies illustrating the conundrum of who to treat, when, and how. For example, a 10-year-old girl with SMA type 2 started taking nusinersen and noticed improvement, which waned toward the end of the four-month period between doses. “Should we treat her every three months?” asked Finkel. “That’s a hard sell for insurance companies that are struggling to cover the cost of dosing every four months,” he said.

Also, what about patients who have had their spines surgically fused and cannot receive nusinersen via lumbar injections? Data from Aravindhan Veerapandiyan, University of Rochester Medical Center, New York, suggested cervical puncture could work as an alternative. He succeeded in delivering five standard 12 mg/5 ml doses of nusinersen into the CSF of three patients in this way. However, as Finkel noted, it is not yet known if this route of administration will be effective. Others wrestled with whether there should be an age or stage limit for treatment. “Is there a population for whom it makes no sense to use this expensive drug?” asked Day, describing a nearly paralyzed man with SMA2 who gained mobility of a finger and reported improved stamina and a stronger voice after treatment. On the other end of the spectrum, clinicians are grappling with whether patients with mild or nonexistent symptoms should be treated. For example, a toddler who carries homozygous SMN1 mutations and four good copies of the SMN2 gene scored above average in motor tests, but is steadily losing her edge. Day asked, should she be treated?

Familial Amyloid Polyneuropathy

In contrast to type 1 SMA, familial amyloid polyneuropathy (FAP) is a rare, slowly progressing degenerative condition caused by accumulation of amyloid fibrils of transthyretin in a multitude of tissues, including peripheral nerves and the heart. Patients in stage 1 have difficulty walking, and by stage 2 can no longer walk unassisted, are in pain, and may have other symptoms, from diarrhea to heart problems. When the latter predominates, the disease is referred to as familial amyloid cardiomyopathy, or FAC. Because amyloid deposits build up slowly, symptoms appear any time from early adulthood to old age, but progression from stage 1 to 2 takes only a couple of years.

Ionis developed inotersen to knock down transthyretin transcripts, and last year reported that this ASO halted progression of FAP. At AAN, John Berk, Boston University, summarized data from 172 adult participants with FAP stage 1 or 2 in the NEURO-TTR Phase 3 trial. This 15-month trial assessed efficacy and safety of weekly subcutaneous injections of 300 mg inotersen (May 2017 news). Participants were randomized 2:1 to treatment and placebo, and assessed for change on their baseline score on the Norfolk Quality of Life Diabetic Neuropathy (Norfolk QOL-DN) scale, which measures the impact on patients’ lives caused by nerve fiber degeneration, and on the modified neuropathy impairment score +7 (mNIS+7), which measures nerve function, muscle strength, and pain. The Norfolk QOL-DN ranges from 1–136 points, the mNIS+7 from 1–346; on both, higher scores are worse. In the treatment arm, 37 percent of people improved over baseline in the mNIS+7, and 50 percent improved on the Norfolk QOL-DN. How about the placebos? This is only meaningful compared to them. Eighty-one percent of participants completed the trial, and of those, 95 percent chose to continue receiving treatment in an ongoing open-label extension.

All the same, Berk noted some serious safety issues. Three patients suffered severe kidney malfunction. Three patients had thrombocytopenia, i.e., extremely low platelet counts, believed to be related to the drug. Even worse, one died from a subsequent intracerebral hemorrhage. The two others recovered after stopping the ASO and taking corticosteroids. Berk noted that the patient who died had received inotersen for nine weeks with no monitoring of platelet count. “The reason for the precipitous drop in platelets remains unclear,” he said. No additional serious cases of thrombocytopenia have developed since then, Berk said, suggesting that with proper monitoring, platelet numbers can be controlled.

Thomas Brannagan, Columbia University, New York, said at AAN that with weekly monitoring in the extension study, ASO dosing is now being stopped or reduced if platelets drop below a set threshold. Similarly, kidney problems appear to be manageable with routine testing. Nevertheless, three patients in the extension suffered serious adverse events considered to be related to treatment. Brannagan did not say what these events were.

His poster detailed interim efficacy results from the extension as of September 15, 2017. The study included 134 patients with a mean age of 64 years, of whom 85 had been on inotersen and 49 on placebo. Among the former, mNIS+7 scores inched up nine points; that is 41 points less than projected based on progression in the placebo group (image below). Similarly, the mean Norfolk QOL-DN scores worsened by four points, about 17 points less than placebo projection. Patients who switched from placebo to inotersen also benefitted, but their gains were more modest, with mNIS+7 scores worsening by 31 points on average, and Norfolk QOL-DN scores by 11 points. “The impression is that the earlier the intervention, the greater the chance of improvement,” said Berk. However, most of the improvement occurred before the open-label extension. During the extension, people who had been on inotersen continuously seemed to plateau, or even begin to deteriorate again, indicating the drug seems to delay, but not stop, the disease process. Inotersen is now under priority review for FDA approval.

Antisense Against Amyloidosis. People with transthyretin amyloidosis who took inotersen continuously scored better (blue) on neurological (left) and quality of life (right) tests than those on placebo (red). After switching to inotersen they did better than projected (dashed line). [Courtesy of John Berk, Boston University.]

Alnylam Pharmaceuticals in Cambridge, Massachusetts, has adopted a different strategy to knock down transthyretin. Patisiran, a small RNA encapsulated in a lipid nanoparticle, destroys transthyretin mRNA by engaging the gene-silencing complex RISC. At AAN, David Adams, National Reference Centre for FAP INSERM in Paris, summarized results from the Phase 3 APOLLO trial (Adams et al., 2017). Patients in APOLLO had FAP caused by a variety of TTR mutations. Most had heart damage, including thickened ventricle walls. They received intravenous injections of 0.3 mg/Kg patisiran every three weeks.

More than half of the 225 participants on patisiran, versus only 4 percent on placebo, registered drops on the mNIMS+7 after baseline. The improvements surfaced nine months into treatment, and average scores continued to improve until the end of the study at 18 months. Adams said the results suggested reversal of disease. A press release from Alnylam additionally claims a positive correlation between TTR knockdown and improvement in neurologic function. These data were presented at the 16th International Symposium on Amyloidosis, held this past March in Kumamoto, Japan. Secondary outcome measures, including Norfolk QOL-DN scores and gait speed, also reportedly improved on patisiran.

The treatment appeared safe. Adams said the frequency of serious adverse events was similar in the groups, with deaths in the placebo arm occurring at 7.8 percent versus 4.7 percent in the treatment arm. There were no signs of liver or kidney problems, nor thrombocytopenia. The majority of adverse events were mild to moderate peripheral swelling or reactions at the injections site, which rarely caused patients to stop treatment.

Adams reported an association between patisiran treatment and reduced thickness of the ventricular wall in a subgroup of 126 patients who had abnormally large left ventricular walls at baseline. The patients’ heart functions improved, and they had lower levels of a cardiac stress biomarker called N-terminal pro b-type natriuretic peptide in the blood.

How do inotersen and patisiran compare? Their trials were not run side by side, used different endpoints and methodologies, and recruited patients with different characteristics. Different safety concerns have arisen for each of the drugs, although as of now they both appear largely safe and well-tolerated. Whereas inotersen is delivered subcutaneously, patisiran requires intravenous injection. Alnylam is developing a new RNAi therapeutic that can be delivered subcutaneously, which Adams said potently and durably reduced TTR in Phase 1.—Marina Chicurel

References

News Citations

- At AAN, Sights Set on Antisense Therapies for Diseases of the Brain

- Positive Trials of Spinal Muscular Atrophy Bode Well for Antisense Approach

- What Price Success? Ionis Drug Worked in Phase 3 but Had Serious Side Effects

Paper Citations

- Finkel RS, Mercuri E, Darras BT, Connolly AM, Kuntz NL, Kirschner J, Chiriboga CA, Saito K, Servais L, Tizzano E, Topaloglu H, Tulinius M, Montes J, Glanzman AM, Bishop K, Zhong ZJ, Gheuens S, Bennett CF, Schneider E, Farwell W, De Vivo DC, ENDEAR Study Group. Nusinersen versus Sham Control in Infantile-Onset Spinal Muscular Atrophy. N Engl J Med. 2017 Nov 2;377(18):1723-1732. PubMed.

- Mercuri E, Darras BT, Chiriboga CA, Day JW, Campbell C, Connolly AM, Iannaccone ST, Kirschner J, Kuntz NL, Saito K, Shieh PB, Tulinius M, Mazzone ES, Montes J, Bishop KM, Yang Q, Foster R, Gheuens S, Bennett CF, Farwell W, Schneider E, De Vivo DC, Finkel RS, CHERISH Study Group. Nusinersen versus Sham Control in Later-Onset Spinal Muscular Atrophy. N Engl J Med. 2018 Feb 15;378(7):625-635. PubMed.

- Adams D, Suhr OB, Dyck PJ, Litchy WJ, Leahy RG, Chen J, Gollob J, Coelho T. Trial design and rationale for APOLLO, a Phase 3, placebo-controlled study of patisiran in patients with hereditary ATTR amyloidosis with polyneuropathy. BMC Neurol. 2017 Sep 11;17(1):181. PubMed.

External Citations

Further Reading

Papers

- King NM, Bishop CE. New treatments for serious conditions: ethical implications. Gene Ther. 2017 Sep;24(9):534-538. Epub 2017 May 3 PubMed.

- Gerrity MS, Prasad V, Obley AJ. Concerns About the Approval of Nusinersen Sodium by the US Food and Drug Administration. JAMA Intern Med. 2018 Apr 30; PubMed.

- Charleston JS, Schnell FJ, Dworzak J, Donoghue C, Lewis S, Chen L, Young GD, Milici AJ, Voss J, DeAlwis U, Wentworth B, Rodino-Klapac LR, Sahenk Z, Frank D, Mendell JR. Eteplirsen treatment for Duchenne muscular dystrophy: Exon skipping and dystrophin production. Neurology. 2018 May 11; PubMed.

Annotate

To make an annotation you must Login or Register.

Comments

No Available Comments

Make a Comment

To make a comment you must login or register.