Aβ, Tau, and Other AD Markers Altered in COVID

Quick Links

Does COVID-19 increase the risk of dementia? While that will take decades to answer, researchers are beginning to unravel how this disease might injure the brain. At the Alzheimer’s Association International Conference held in July in Denver and online, researchers described lingering cognitive deficits and biomarker changes in people six months after COVID infection. Thomas Wisniewski and colleagues at the New York University School of Medicine found lower plasma Aβ42 and higher tau levels in "neuro-COVID" cases than those without brain symptoms. Nelly Kanberg, University of Gothenburg, Sweden, saw plasma neurofilament and glial fibrillary acidic protein rise in the weeks following severe COVID, regardless of neurological problems, then normalize by six months. Likewise, Patrick Smeele and Lisa Vermunt of Amsterdam UMC saw plasma NfL rise then fall during the first few weeks of ICU stays. What this means for long-term dementia risk, if anything, remains unclear.

- Plasma NfL, GFAP up in severe COVID, normalized by six months.

- Serum Aβ42 lower, tau higher in cases with neurological symptoms.

- Six months post-COVID, half of all survivors still had a cognitive impairment.

Biomarker Trajectories

Some people experience cognitive problems and other neurological symptoms during COVID. Could annoying brain fog foretell something more sinister? During the illness, total tau, NfL, and GFAP rise in the cerebrospinal fluid, while the latter two are known to climb in the blood (Jan 2021 news; Espíndola et al., 2021). While most research has focused on hospitalized people, one small study showed an uptick in CSF NfL and GFAP in the mildly sick (Virhammar et al., 2020). This hints that the brain may be under attack. How long might these insults last?

So far, some researchers have followed patients for six months after either testing positive or going home from the hospital. Wisniewski and colleagues measured blood markers in 310 adults with severe COVID after they went home from one of four NYC hospitals. Of those, 158 had had neurological symptoms, aka neuro-COVID, during their hospital stay; 152 did not. Average ages were 70 and 73, respectively; in both groups more than half were men.

After six months, people with neuro-COVID had 1.5-times more total tau and p-tau181, half as much Aβ42, and six times higher total tau/Aβ42 ratios in their plasma. Aβ40 levels were similar regardless of neurological symptoms. Does this mean people with neuro-COVID are at risk for dementia? Only a few cohorts have reported Aβ and tau markers so far, and the jury is still out (see below for commentary). Wisniewski was unavailable for comment

Wisniewski's group also measured markers of neuronal injury after six months. Neuro-COVID cases still had 2.5 times more NfL and 1.5 times more GFAP than people who had had COVID without neurological symptoms. This may indicate lingering damage, especially in the former group.

Did biomarkers return to normal in COVID cases compared to people who never caught the virus? Kanberg and colleagues led by Magnus Gisslén at UGothenburg suggest so in their poster, and a paper published July 29 in EBioMedicine. They recorded neurological symptoms and collected blood from 51 controls and 24, 28, and 48 adults who had had mild, moderate, and severe COVID, respectively, at the Sahlgrenska University Hospital in Gothenburg. Sixty-eight percent were men, average age 56. Kanberg followed them for up to 7.5 months after symptom onset. The scientists analyzed plasma NfL, GFAP, and growth factor GDF-15, also called MIC-1, a marker of organ and vascular brain injury (McGrath et al., 2020).

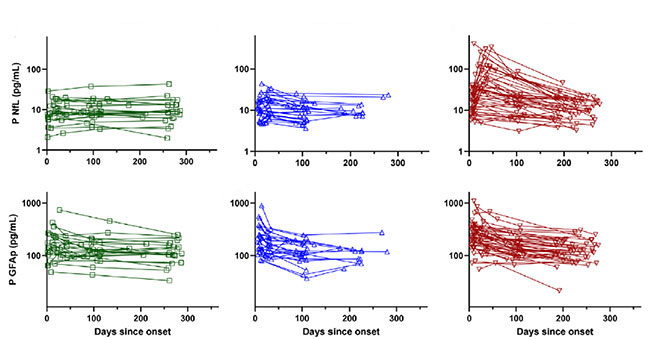

Compared to controls, mild COVID patients had no change in their plasma markers. Moderately and severely ill people had higher GDF-15 concentrations. As for neuronal injury markers, GFAP levels jumped during the first few weeks of moderate and severe illness, then dropped back to normal over the next few months. While NfL remained steady in moderate cases, it soared during the first two months of severe illness, then dropped to normal by six months (see image below). “This pattern could indicate an initial astrocytic reaction followed by lingering neuronal injury,” Kanberg told Alzforum. The scientists did not measure levels of Aβ40, Aβ42, total tau, and p-tau181 in these samples, though Henrik Zetterberg, also at UGothenburg, said they will.

Settling Down

Plasma NfL (top) and GFAP (bottom) mainly remained steady in mild (left) and moderate (middle) COVID cases but spiked in the severely ill (right). Markers normalized by six months. [Courtesy of Kanberg et al., EBioMedicine, 2021.]

Half of the volunteers in the Gothenburg cohort had neurological problems at six months, though biomarkers did not correlate with thise. “NfL and GFAP normalized in every patient, regardless of whether they had long-term symptoms or not,” Kaj Blennow, U Gothenburg, told Alzforum. Kanberg and colleagues concluded that long-term neurological problems from COVID do not indicate ongoing CNS injury or neurodegeneration.

Smeele, Vermunt, and colleagues led by Charlotte Teunissen at Amsterdam UMC measured an NfL upsurge in blood taken from 31 adults who had severe COVID and were admitted to the university’s medical center. The researchers took blood samples from the volunteers every few days for up to four weeks. The average age was 63, 70 percent were men. Within 90 days of admission, seven had died. In survivors, plasma NfL levels peaked around 2½ weeks after admission into the ICU; in those who died, plasma NfL levels kept climbing for at least 3½ weeks (see image below).

Diverging Paths

Logarithmic spaghetti plots of individual COVID patients show plasma NfL peaked sooner, and at lower levels, in survivors (thick yellow line) than those who perished (purple line). [Courtesy of Patrick Smeele, Amsterdam UMC.]

Likewise, Meredith Hay, University of Arizona, Tucson, and colleagues reported higher serum NfL in COVID ICU patients than in people who were there for other reasons, see preprint posted May 2 on medRxiv (Hay et al., 2021). Of 100 people admitted to the university hospital, 89 had COVID. On average, people with the virus had 12 times the amount of NfL in their blood as those admitted for other reasons, 230 pg/mL in COVID ICU vs. 19 pg/mL. The level was even higher in people with COVID who also had cardiovascular disease and diabetes. The authors thought this could mean that widespread inflammation in the body could fuel the neuronal damage seen in COVID, and hint at whose cognition stays at risk later in life.

COVID and Cognition

People have reported neurological symptoms after contracting the virus, with some persisting for weeks or months (Apr 2021 conference news). How common are these?

Wisniewski and colleagues found neurological disorders in 13.5 percent of 4,491 adults hospitalized with COVID in New York City (Frontera et al., 2021). The researchers phoned up 382 survivors six months later to follow up. Half were still struggling performing daily activities, or their cognition as judged by the Montreal Cognitive Assessment had declined. People who had had neuro-COVID struggled more with activities and disability, per the modified Rankin Scale, but their cognition had weakened similarly to COVID cases who had not had neurological symptoms (Frontera et al., 2021). Wisniewski drew on this cohort for the biomarker analysis.

For their part, scientists led by Yan-Jiang Wang and Juan Liu at the Third Military Medical University, Chongqing, China, detected cognitive deficits in 10 percent of 1,301 non-severely and 238 severely ill COVID patients older than 60 from Wuhan (Liu et al., 2021). Six months after being discharged from the hospital, COVID cases scored worse on the Telephone Interview of Cognitive Status-40 (TICS-40) than did the 466 uninfected controls. Non-severe cases and controls scored similarly: 5 percent were in the MCI range and less than 1 percent in the dementia range. Severely ill people scored worse, with 25 percent in the MCI range and 11 percent in the dementia range.

At AAIC, Gabriel de Erausquin, University of Texas Health, San Antonio, presented striking results from an Argentinian cohort of 330 COVID cases, ranging from mild to severe. Four to seven months after testing positive, researchers assessed participants using the global Clinical Dementia Rating scale and tests to gauge memory, executive function, orientation, and language. While no one in this cohort had complained of having memory or cognitive issues before COVID, 60 percent did after the infection. “This is 10 times the prevalence of impairment in the older general population,” de Erausquin said. While one-third of those participants scored poorly in one cognitive domain, the remaining two-thirds struggled in multiple domains.

For Göran Hagman, Miia Kivipelto, and colleagues at the Karolinska University Hospital in Sweden, COVID outcomes were less clear. They tested 32 adult COVID survivors three months after they were discharged from the ICU. Despite several participants expressing concern about their cognition, testing showed no pattern. “Some patients were cognitively intact, but others had deficits in attention and executive function,” Kivipelto told Alzforum.

The researchers did find signs of microvascular injury via structural MRI. They are now asking if this injury relates to cognitive problems. “We want to learn if brain damage and poorer cognitive scores match with the subjective cognitive decline people are reporting,” Kivipelto said. To figure out what is going on at a deeper level, Zetterberg and de Erausquin plan to measure neuronal injury and neurodegeneration markers in blood samples taken from the Swedish and Argentinian volunteers.

Into the Unknown

Many people fear long-term effects from contracting COVID, especially brain fog and other neurological consequences. What do the spikes in the markers measured so far mean for future dementia risk? Zetterberg found it reassuring that the markers normalize within six months. “I feared that SARS-CoV-2 would induce ongoing neuronal injury,” he told Alzforum.

Then what causes the neurological symptoms of long COVID? “Lasting symptoms may indicate lingering brain network disturbance induced by the virus rather than frank CNS injury,” said Zetterberg, who added that other infections can leave a person with brain fog for months without evidence of simultaneous brain injury.

Other researchers thought that how severely ill a person is, not COVID itself, may predict dementia risk. “Hospitalization, in general, is a risk factor for dementia, but we do not know why,” Vermunt said. “How sick you get and how you recover may predict who is at risk of future dementia,” Smeele added. Kanberg agreed, noting that the rise in NfL and GFAP in severe COVID cases may be prognostic. “This may mean they are prone to future neuronal injury, so we could track these people to see if they have any long-term problems or develop dementia,” she said.

Vermunt wondered if the opposite might be true—that people who already have prodromal dementia are more likely to have worse COVID. “Perhaps this was why they developed severe disease, but that needs to be answered with population-based research,” she said.—Chelsea Weidman Burke

References

News Citations

Paper Citations

- Virhammar J, Nääs A, Fällmar D, Cunningham JL, Klang A, Ashton NJ, Jackmann S, Westman G, Frithiof R, Blennow K, Zetterberg H, Kumlien E, Rostami E. Biomarkers for central nervous system injury in cerebrospinal fluid are elevated in COVID-19 and associated with neurological symptoms and disease severity. Eur J Neurol. 2020 Dec 28; PubMed.

- Frontera JA, Sabadia S, Lalchan R, Fang T, Flusty B, Millar-Vernetti P, Snyder T, Berger S, Yang D, Granger A, Morgan N, Patel P, Gutman J, Melmed K, Agarwal S, Bokhari M, Andino A, Valdes E, Omari M, Kvernland A, Lillemoe K, Chou SH, McNett M, Helbok R, Mainali S, Fink EL, Robertson C, Schober M, Suarez JI, Ziai W, Menon D, Friedman D, Friedman D, Holmes M, Huang J, Thawani S, Howard J, Abou-Fayssal N, Krieger P, Lewis A, Lord AS, Zhou T, Kahn DE, Czeisler BM, Torres J, Yaghi S, Ishida K, Scher E, de Havenon A, Placantonakis D, Liu M, Wisniewski T, Troxel AB, Balcer L, Galetta S. A Prospective Study of Neurologic Disorders in Hospitalized Patients With COVID-19 in New York City. Neurology. 2021 Jan 26;96(4):e575-e586. Epub 2020 Oct 5 PubMed.

- Frontera JA, Yang D, Lewis A, Patel P, Medicherla C, Arena V, Fang T, Andino A, Snyder T, Madhavan M, Gratch D, Fuchs B, Dessy A, Canizares M, Jauregui R, Thomas B, Bauman K, Olivera A, Bhagat D, Sonson M, Park G, Stainman R, Sunwoo B, Talmasov D, Tamimi M, Zhu Y, Rosenthal J, Dygert L, Ristic M, Ishii H, Valdes E, Omari M, Gurin L, Huang J, Czeisler BM, Kahn DE, Zhou T, Lin J, Lord AS, Melmed K, Meropol S, Troxel AB, Petkova E, Wisniewski T, Balcer L, Morrison C, Yaghi S, Galetta S. A prospective study of long-term outcomes among hospitalized COVID-19 patients with and without neurological complications. J Neurol Sci. 2021 Jul 15;426:117486. Epub 2021 May 12 PubMed.

Further Reading

Papers

- Huang L, Yao Q, Gu X, Wang Q, Ren L, Wang Y, Hu P, Guo L, Liu M, Xu J, Zhang X, Qu Y, Fan Y, Li X, Li C, Yu T, Xia J, Wei M, Chen L, Li Y, Xiao F, Liu D, Wang J, Wang X, Cao B. 1-year outcomes in hospital survivors with COVID-19: a longitudinal cohort study. Lancet. 2021 Aug 28;398(10302):747-758. PubMed.

Primary Papers

- Kanberg N, Simrén J, Edén A, Andersson LM, Nilsson S, Ashton NJ, Sundvall PD, Nellgård B, Blennow K, Zetterberg H, Gisslén M. Neurochemical signs of astrocytic and neuronal injury in acute COVID-19 normalizes during long-term follow-up. EBioMedicine. 2021 Aug;70:103512. Epub 2021 Jul 29 PubMed.

Annotate

To make an annotation you must Login or Register.

Comments

No Available Comments

Make a Comment

To make a comment you must login or register.